Bunker Hill: Amphibious and Infantry operations

Background

The Seven Years War ended with Britain ascendant in North America. Almost immediately, difficulties arose in administering this vast territory. Economic factors necessitated reform: in 1750 the population of British North America was 1.2 million, nearly doubling to 2.3 million in 1770.[i] New England’s growing population had outstripped its domestic wheat production. In 1763, Britain’s national debt totaled £130 million. Military costs in American spiraled, from £70,000 annually in 1748, to £350,000 at the close of the Seven Years War.[ii]

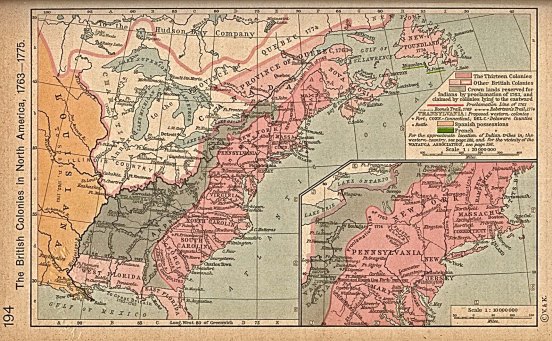

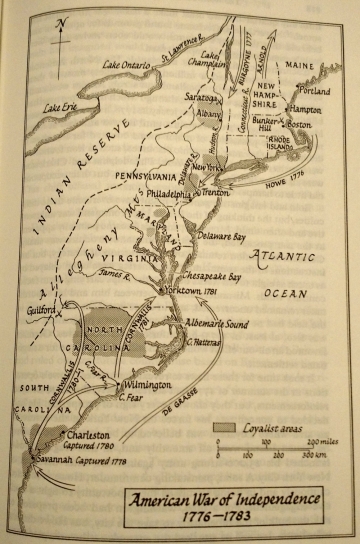

America at the end of the Seven Years War, 1763.[iii]

To offset these costs the Grenville government reformed Britain’s policy on trade control with the American colonies. The steady rise in Royal taxation and duties on British imports following the Treaty of Paris (1763), was reflected in the expansion of the Molasses Act (1733) as the Sugar Act of 1764,[iv] which included restrictions on shipping in an effort to limit smuggling.[v] The unpopular Stamp Act and Quartering Act of 1765 followed shortly. The Stamp Act, expected to generate £100,000 towards offsetting defence costs, was passed in addition to a battery of subsidies and other reforms aimed at stimulating trade between Britain and the colonies.[vi] Defence spending was cut, starting with the naval estimate, which declined from £2.8 million in 1766 to £1.5 million in 1768.[vii]

American boycotts on imports, as a result of the Stamp Act, led to the ascension of the Rockingham government. The Stamp Act was repealed, and replaced, by the Declaratory Act in March 1766.[viii] Next, Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend’s Acts of 1768 made modifications to the duties on paper, glass and tea, and was expected to generate £40,000 a year.[ix] Captured smugglers were made liable for seizure of property, including their ships. This situation was not acceptable to the wealthy Bostonian merchant class, amongst their supporters men such as John Hancock (whale oil, tea, Madeira) and Samuel Adams (heir to a brewing establishment).[x] Adams and James Otis circulated a letter in opposition to parliamentary taxation early in 1768.[xi] In the summer of 1768, General Thomas Gage was forced to dispatch troops to Boston from Halifax to maintain order.[xii]

Boston, population 16,000 in 1775, was the significant port in Massachusetts, the third largest port on the North Atlantic seaboard after New York and Philadelphia.[xiii] Boston was a center for opposition to the British colonial government. By 1775 there appeared a significant group of urban poor: Boston’s poor relief costs had quadrupled since 1740 and its population was no longer growing.[xiv] In 1771 the top 10% of Bostonians in the merchant and professional classes owned 60% of the city’s wealth.[xv]

The Sons of Liberty society, formed in Boston and New York, was opposed to the expansion of British economic and naval intervention in American trade.[xvi] There was a vested interest in maintaining New England’s laissez-faire status: while in 1763 “the average Briton paid 26 shillings” per annum in taxes, the equivalent for Massachusetts taxpayers was only one shilling.[xvii] Indeed, the New Englanders represented one of the wealthiest societies in the world at the time. Bootleggers out of Boston, Newport and New York continued to make a killing trading corn, cattle, lumber and codfish for sugar, rum and molasses, in the French West Indies.[xviii]

Paul Revere’s engraving of two regiments of British troops unloading at Boston in 1768.[xix]

Bostonians continued to protest the expansion of British tariffs and trade restrictions, despite Lord North’s January 1770 reduction on duties for commodities other than tea.[xx] When harassed British soldiers opened fire on a crowd and were generally acquitted in the following inquiry- what became known as the Boston Massacre of March 1770- tensions ran high between the Boston garrison and the colonials.[xxi] Shortly thereafter, Benjamin Franklin wrote for the London Chronicle, in November 1770, stating, “the Parliament of Britain hath no right to raise revenue from them [the Colonies] without their consent”.[xxii] In 1772 the sloop Gaspee was burned by John Brown and followers, after the sloop ran aground while chasing merchant shipping near Providence, Rhode Island.[xxiii]

The Tea Act of 1773 attempted to foist surplus British East India Company tea off on the Atlantic colonies (ironically tea prices were deflated in part by an American boycott of the Townshend Acts), thus keeping prices low and diminishing smuggling revenue.[xxiv] In response, the Sons of Liberty, including John Hancock and Samuel Adams, organized the Boston Tea Party of 16 December 1773. 342 boxes of BEIC tea, valued at £15,000 were destroyed.[xxv] The resulting Port Act of March 1774, and second Quartering Act in June, essentially established military control over the port and the naval blockade of Boston, to remain in force until an indemnity was paid for the tea.[xxvi] General Thomas Gage was made emergency governor.[xxvii] While the British maintained control over Boston, the surrounding countryside was of questionable loyalty. On July 1st, in Boston, Vice-Admiral Samuel Graves arrived as C-in-C North American Squadron aboard HMS Preston, and accompanied by the 5th and 35th regiments.[xxviii]

General Thomas Gage by Jeremiah Meyer, circa 1770s.[xxix]

The Quebec Act of 1774 closed the Canadian frontier to the American settlers, and recognized the right to Catholic practice by the French-Canadians, upsetting the anti-papist colonialists in New England.[xxx] The Massachusetts Government Act came into effect in August 1774 and provided George III with the authority to appoint the members of the formerly elected Massachusetts Governor’s Council. Pursuant to this act, Governor Thomas Gage dissolved the Provincial Assembly then meeting in Salem in October 1774.[xxxi] That same month he fortified his position in Boston.[xxxii] The concern was to secure Boston as a port of entry for the Army’s supplies.[xxxiii] Meanwhile, on 5 September 1774 the First Continental Congress was convened at Philadelphia, and in December of that year a group of Sons of Liberty supporters raided Forts William and Mary at Portsmouth, stealing cannon, muskets and powder.[xxxiv]

The former Provincial Assembly, now the Concord based Massachusetts Provincial Government, raised its own militia and was preparing to resist the British.[xxxv] The result was that in February 1775 Massachusetts was declared to be in a state of rebellion. Lord North issued the Conciliatory Resolution on 27 February 1775, granting duties payable directly to the colonies and parliamentary regulation on trade only, so long as the colonies agreed to pay something for defence.[xxxvi]

It was too little too late for the Americans. Local governments now began to supersede their imperial governors, starting with New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia and South Carolina.[xxxvii] Gage, in Boston, received secret orders around the middle of April 1775 to the effect that he was to “arrest and imprison the principal actors & abbettors” meaning the Provincial Congress then at Concord, and probably including Sam Adams and John Hancock then hiding in Lexintgon.[xxxviii] Gage was opposed to antagonizing the continentals, however, he suffered a disconnect with the government in London, which believed that a show of force would reduce the rebellion.[xxxix]

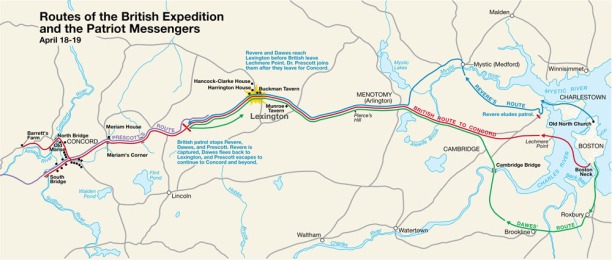

Map of Boston and countryside, showing route of British forces and Patriot messengers to Concord.[xl]

The operation meant to carry out these orders resulted in the first conflict between British forces and the colonial militia, on 19 April 1775: the battles of Concord and Lexington.[xli] British forces deployed from Boston with the objective of capturing suspected militia arms caches at Concord. Colonial messengers, including Paul Revere, were able to tip-off the militia, as well as Adams and Hancock, before the British arrived. Outnumbered, the colonial militia retreated from Lexington to Concord and then to the countryside. The regulars entered Concord shortly afterward and rounded up, and captured or destroyed, several hidden cannon, victuals, and supplies of powder and musket ball.[xlii]

British column enters Concord, 19 April 1775.[xliii]

The militia reformed outside Concord, and backed by companies of Minutemen, were able to confront portions of the British force, inflicting casualties. Realizing that opposition was stiffening, and with the mission to search Concord complete, the British withdrew to Boston. Harassed and ambushed along the way by an increasing numbers of colonials, the British were given an unmistakable message: the continentals were prepared to resist. 259 soldiers had been killed or wounded in the retreat from Concord.[xliv] The militia, now numbering over 10,000 men, moved to invest the British base at Boston, thus initiating the 11 month long Siege of Boston.[xlv]

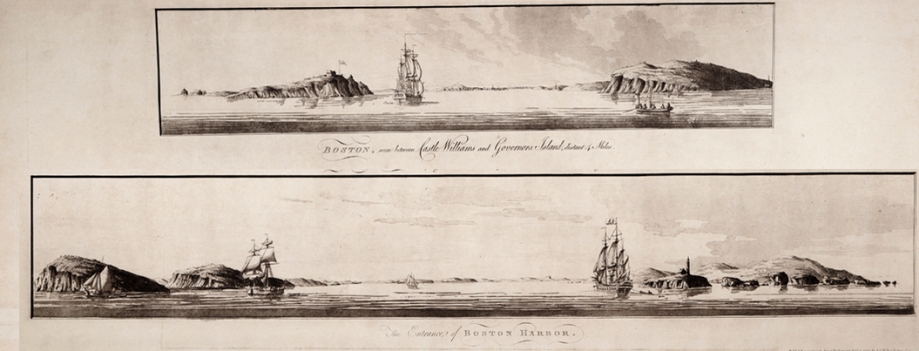

Views of entrance to Boston Harbour. Boston, seen between Castle Williams and Governors Island, distant 4 miles. 1777 by J. F. W. Des Barres.[xlvi]

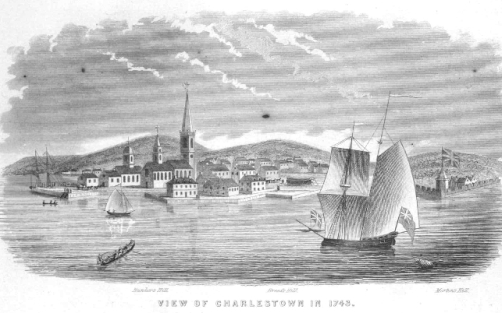

Charlestown in 1743.[xlvii]

The Siege

With Boston under siege there was no going back. On 22 April, the Massachusetts shadow government called up 30,000 men.[xlviii] The Second Continental Congress convened on 10 May 1775, and the colonies continued to assemble their contingents through the summer. The British could draw only limited forces from their small standing army of 38,000.[xlix] Nevertheless, reinforcements arrived from Britain to supplement Gage’s small force of 3,000, including Generals Sir William Howe, John Burgoyne, and Henry Clinton; bringing the total force up to 8,000 regulars.[l]

General William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe, by Richard Purcell, 10 May 1778.[li]

The American force, now numbering 20,000 men, had largely assembled around Boston, under the overall command of General Ward. A prisoner exchange took place on 6 June, and on the 12th Gage declared martial law, simultaneously offering a general pardon; Samuel Adams and John Hancock excepted.[lii]

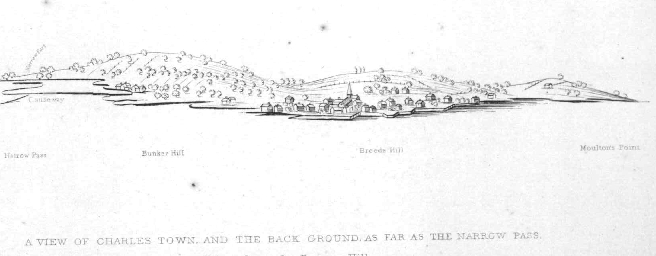

View of Charlestown and the Charlestown Peninsula, 1775, showing the isthmus, Bunker Hill, Breed’s Hill and Moulton’s Point.[liii] Moulton’s Point rose only 35 feet above sea level, Breed’s hill was 75 feet in elevation, and Bunker Hill 110 feet, providing an unobstructed view of Boston.[liv]

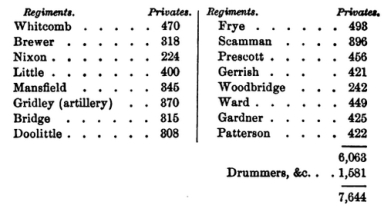

The Second Continental Congress now authorized the American Continental Army and appointed George Washington as General and Commander-in-Chief on 15 June, his commission going through on the 17th.[lv] On 13 June at Ward’s HQ, Cambridge, information was received indicating that General Gage intended to take control of the Charlestown peninsula.[lvi] By June 15th it was known that Gage, at a council of war, had picked 18 June for the start of the Charlestown operation; and the Massachusetts authorities therefore deployed the Continental Army in preparation for a showdown.[lvii] The roster for the Continental detachment at Bunker Hill is here.[lviii]

Plan of Action for the Bunker Hill operation, by Lieut. Page of the Engineers, Major-General Howe’s Aide de Camp.[lix] Note location of “Bunker’s Hill” relative to Breed’s: reversed by Page.[lx]

Deployments

The spoiling plan called for the occupation of Bunker Hill and the heights overlooking Charlestown, although, in the event, the central Breed’s Hill was selected. General Ward and General Warren, at Army HQ, were opposed to a heavy engagement. They knew the Continental Army was short on powder: the Army’s entire supply of powder amounted to 27 half barrels with another 36, “a present from Connecticut”.[lxi]

Regiments accounted at Cambridge HQ.[lxii]

General Israel Putnam commanded the division from which the American contingent that was to occupy the peninsula was drawn. Detachments from Massachusetts and Connecticut were selected, led by Colonel William Prescott and supported by Colonels Frye and Bridge.[lxiii] Captain Thomas Knowlton was attached with 200 Connecticut rangers. Support was provided by Colonel Richard Gridley, chief engineer, “with a company of artillery”- 49 men.[lxiv] The total force was at least 1,200 strong, carrying 24 hours of rations, and accompanied by all the entrenching tools in Cambridge.[lxv] Prescott’s orders were to fortify the Charleston peninsula, starting at Bunker Hill. He could expect support and fresh rations the following morning.[lxvi] As this contingent deployed it was joined by Major Brooks with more infantry and another company of artillery. Captain Nutting was dispatched with a small detachment of Connecticut men to investigate Charlestown, and Captain Maxwell of Prescott’s regiment was sent to patrol the shore and observe the Royal Navy warships in the Harbour.

Plan of Battle for Bunker Hill, Library of Congress[lxvii]

These ships were under the command of Vice-Admiral Samuel Graves:[lxviii] HMS Somerset, 68, (3rd rate, crew 520, built 1748) Captain Edward Le Cras; Cerberus, 36, (built 1770) Captain Chads; Glasgow, 24, (6th rate, 130 men, built 1757) Captain William Maltby; sloop Lively, 20 guns, 130 men, Captain Thomas Bishop; sloop Falcon, Captain Linzee; and the transport Symmetry with 18 or 20 nine-pounder guns, plus lesser gunboats and floating batteries.[lxix]

All afternoon on the 16th and morning on the 17th the Americans developed their entrenchments. By the morning of the 17th a small redoubt had been established on Breed’s Hill.[lxx]

The Battle

It was a hot day, with a light breeze blowing. The Continentals lacked water and were low on rations. At 9 am, HMS Lively, accompanied by Glasgow, as well as cannon from the shore batteries and howitzers from Copp’s hill, opened fire on the Continental positions.[lxxi] The Americans arranged a council of war: no reinforcements had arrived, and the British were evidently preparing to confront them.[lxxii] With rations running out, Major John Brooks was dispatched to HQ to report on the situation, where he arrived at 10 am. Along the way, Brooks passed General Putnam who was racing towards the Charlestown Heights to support Prescott with a detachment of one third of Colonel Stark’s regiment. Putnam arrived at the redoubt on horseback not long afterwards. Putnam’s orders were for the entrenching tools to be sent to the rear, with the exception for a group to start fortifying Bunker Hill, which had hitherto been ignored.[lxxiii]

At 11 am the rest of Stark’s regiment went in, along with Colonel Read’s fellow New Hampshire regiment.[lxxiv] Detachments from Colonels Brewer, Nixon, Woodbridge, and Major Moore followed. Little, Whitcomb, and Lt. Col. Buckminster made appearances with more handfuls of men. [lxxv] Joseph Warren now arrived, serving under Prescott, and encouraging the defenders of the redoubt. Ward continued to feed reinforcements to the heights throughout the day, however, for the duration of the battle there were no more than 1,400 Americans and their 6 guns on the field. In addition to the shortages of powder, the urgency of the situation revealed weaknesses at Army HQ: critical was a shortage of adequate horses for the purpose of message dispatch.[lxxvi]

Plan of Charlestown peninsula, showing Battle of Bunker Hill, produced in 1775.[lxxvii]

Meanwhile, Gage called a council of war and the plan of operations was rushed to decision. Clinton and the majority of the council favoured a deployment at the isthmus. Gage opposed this on the concern that it would place the British detachment between two armies; Prescott’s detachment and Ward. Gage favoured a frontal attack, and issued orders to that effect at 10 am.[lxxviii] This deployment has generally been regarded as a mistake: not only did it force a frontal assault of the Continental positions, but to compound errors, it left the Continentals free to reinforce, or withdraw, through the isthmus. Furthermore, General Putnam, in overall command of the division to which Prescott was attached, had failed to fortify Prospect Hill north of the isthmus, and did not do so until 18 June. Thus, had the British deployed to the neck of the peninsula, Prescott would have found his detachment cut off from Ward, running low on rations, and dangerously exposed to the guns of the Royal Navy.[lxxix]

Amphibious movements

The British intended to warp HMS Somerset closer to the shore to better place the ship for fire support, but, due to the shallow waters, only the frigates, sloops and gunboats could close to provide direct support. HMS Glasgow and the transport schooner Symmetry directed fire against the Charlestown isthmus. Colonel James, Royal Artillery, with two boats equipped with 12 pounder cannon, supported the warships.[lxxx] Meanwhile, HMS Lively, Falcon, and the gunboat, Spitfire, “anchored abreast of… Charlestown, covered the landing of troops, and kept up a well-directed fire”.[lxxxi]

The base of Breed’s Hill was swept with naval fire as the regulars embarked. Gage dispatched ten companies of Grenadiers, ten companies of light-infantry, along with the 5th, 38th, 43rd, and 52nd regiments.[lxxxii] The British disembarked their force of 2,200 men at Charlestown point and took up position on Moulton’s Hill.

Array of American forces for the Battle of Bunker Hill.[lxxxiii]

By about 1 pm, Colonel Prescott could see that the British were deploying towards Mystic River and Charlestown with the intention of flanking the Continental positions by going around the redoubt. He thus dispatched Captain Knowlton with 400 men and two cannon to form works nearer the base of the Bunker Hill, thus cutting off the flanking efforts.[lxxxiv] Knowlton was soon supported by the New Hampshire detachments of Colonels Stark and Reed, together forming a line 900 feet long. Likewise, Captain Nutting was recalled from Charlestown to cover the redoubt’s south flank.

Between 1 and 2pm, General Clinton received orders to deploy from Boston with his detachment from the 47th regiment, plus 400 marines from the first battalion, and additional companies of Light Infantry and Grenadiers.[lxxxv]

Battle of Bunker Hill by E. Percy Moran, 1909.[lxxxvi]

At 3 pm the British forces began their attack with a cannonade from their positions on Moulton’s, followed by an advance by the first two lines.[lxxxvii] General Pigot, with the 28th, 43rd, 47th, 52nd Regiments and Major Pitcairn’s marines, was ordered to take the redoubt on the left while Howe would take the main emplacements on the right. The light-infantry were dispatched to flank along the Mystic.[lxxxviii] The frontal attack was made by the Grenadiers and the 5th and 52nd regiments.[lxxxix] The British reached the Continental lines at about 3:30.

The Americans held fire until the regulars closed to within musket shot, and then unleashed a withering fire that broke the advance of the British. A brief fire-fight ensued, and the British retreated back to their positions at the base of the hill.[xc]

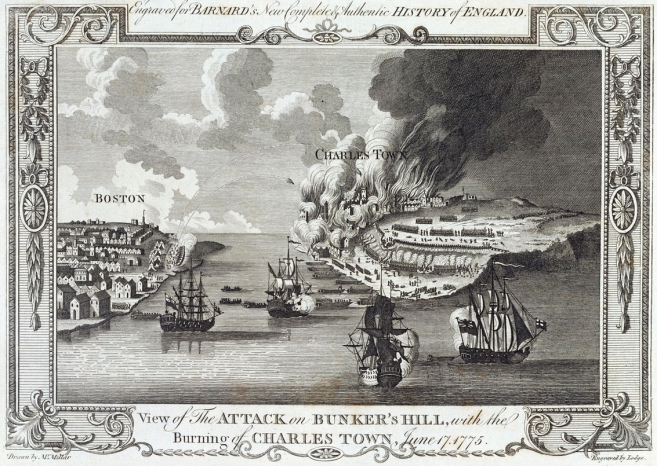

Admiral Graves, alleged to have gone ashore with Howe, at this point inquired if the destruction of Charlestown would be useful in reducing the harassing fire on the left wing.[xci] Howe agreed, and the order was given to fire red-hot shot into the town, while a group of marines from HMS Somerset landed with torches.[xcii] The destruction of Charlestown produced a prodigious quantity of smoke, however, prevailing winds carried the smoke away from the battlefield.

The Battle at Bunker’s Hill by Henry A. Thomas, Circa 1875. Showing the British landings and positions, Charlestown in flames, and HMS Somerset at left.[xciii]

Howe rallied his force and led another assault, the British firing as they went in.[xciv] The line was again held, the Regulars mowed down by the accurate fire of the Americans, although not without loss: “Colonels Brewer, Nixon, and Buckminster were wounded, and Major Moore was mortally wounded.”[xcv] British casualties at this point were over 500 in number.[xcvi] Two of Howe’s aides had been shot.

View of the Attack on Bunker’s Hill, with the Burning of Charles Town. June 17th 1775. Circa 1783, Engraved for Barnard’s New Complete & Authentic History of England.[xcvii]

The supporting naval vessels intensified their fire, torching Charlestown. The fleet developed an intense cannonade of “bombs, chain-shot, ring-shot, and double-headed shot” and was able to clear some of Continental forces from the Breed’s Hill redoubt, likewise destroying some of the Continental positions along the fence-line.[xcviii] In preparation for a third charge, Pigot marshaled elements of the 5th, 38th, 43rd, and 52nd Regiments and returned to attack the redoubt. Clinton was by now in position to reinforce, and Howe ordered a general bayonet charge, this time concentrated against the redoubt.

The Battle of Bunker Hill, by Howard Pyle. 1897. Published by Scribner’s Magazine in February 1898.[xcix]

General Gardner presently arrived at the American lines with 300 men, and was put to task under General Putnam until Gardner was badly wounded. The Continentals were now desperately short on ammunition and lacked bayonets.[c]

The British final effort began between 4 and 5 pm. The regulars advanced under the cover of naval fire and field guns, then received musket fire at close range until the Continentals exhausted their ammunition and began to throw rocks.[ci] The regulars then stormed the American positions with the bayonet, starting with the redoubt, where Major Pitcairn of the marines was killed. Inside the redoubt, Colonel Prescott drew his sword and engaged in hand-to-hand combat, before escaping- but Joseph Warren was killed.[cii] All along the line the Continentals retreated with munitions exhausted. HMS Glasgow, along with the floating batteries stationed in Charles River, swept the retreating Continentals with cannon and grape shot.[ciii] By 5pm the peninsula was under Howe’s control. General Putnam tried to rally the Continentals as they fell back across the isthmus- they were too disorganized and depleted to continue- and thus they regrouped at Prospect Hill.[civ]

John Trumbull’s iconic Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill; painted in 1786.[cv]

Table showing American casualties.[cvi]

Aftermath

441 continental soldiers had been killed, wounded or captured. 5 artillery pieces were lost.[cvii] Doctor Joseph Warren, General, Son of Liberty, Mason, had been killed.

1,054 British soldiers and officers had been killed or wounded: 19 officers killed, 70 wounded, 207 soldiers killed, 304 wounded. [cviii] Gage gave these figures: “1 lieutenant colonel, 2 majors, 7 captains, 9 lieutenants, 15 sergeants, 1 drummer, 191 rank and file killed – 3 majors, 27 captains, 32 lieutenants, 8 ensigns, 40 sergeants, 12 drummers, 706 rank and file wounded.”[cix] Heavily outnumbered by the Continental Army, these were losses the British could ill afford. It was the beginning of the end for Gage’s command; Howe replaced him in October.[cx]

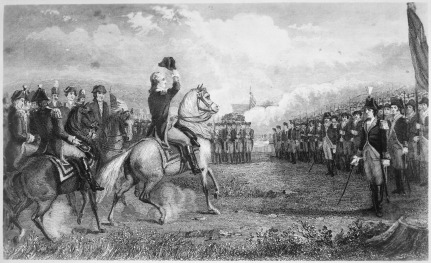

Washington takes command of the American Army at Cambridge, 1775.[cxi]

On 21 June, Washington left Philadelphia and headed for Boston where he assumed command on 3 July 1775.[cxii] In July 1775 the Continental Congress issued John Dickinson’s Olive Branch Petition, and Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms circular, aimed at a reconciliation settlement. The King did not seriously consider the offer.[cxiii] That August in London, George Germain replaced Dartmouth as colonial secretary.[cxiv] In February 1776, in Philadelphia, Thomas Paine anonymously published his Common Sense pamphlet.[cxv] H. H. Brackenridge’s heroic dramatization of the Battle of Bunker Hill appeared the same year.[cxvi]

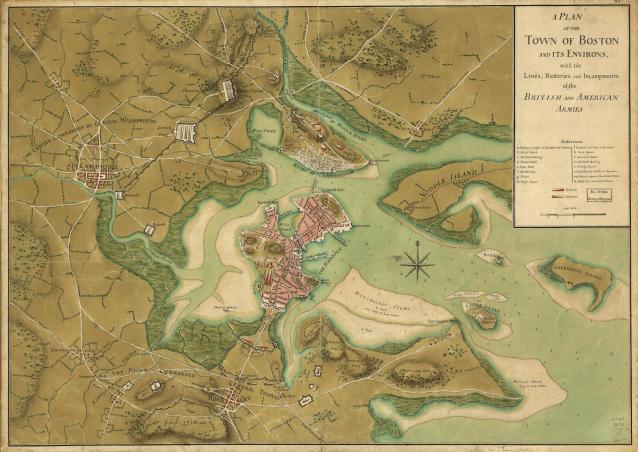

Boston and the surrounding countryside, showing remains of Charlestown, and the location of the American and British commands after June 1775.[cxvii]

Charlestown was reduced to ruin. The heights had been secured, but it was a temporary solution. The battle did not break the siege of the Boston peninsula, nor did it completely secure the heights from Continental attack. Although the British held the captured redoubt atop Breed’s Hill with a small garrison, eventually the Continental Army moved in enough artillery to generate a crisis. On 17 March 1776, Howe was forced to abandon Boston, and he withdrew his army of 9,000 by sea to Halifax.[cxviii]

In May 1776 British intelligence became aware that France planned to support the American revolutionaries with military aid.[cxix]

The Continental Congress votes Independence, July 2, 1776.[cxx]

In the autumn of 1776, General Howe deployed from Halifax with 23,000 men and bested Washington at New York, forcing the latter to withdraw to avoid encirclement.[cxxi] Washington won minor victories and Trenton and Princeton at the end of 1776. By July 1777, Howe confided in General Henry Clinton that he expected the war to last for another year, at least.[cxxii] The Royal Navy was to commence full mobilization in August 1777. In November, General Howe issued a general pardon to all rebels who “surrendered and reaffirmed their allegiance to George III.”[cxxiii] The month before, however, the 1777 campaign came to its distressing close with Burgoyne’s surrender of over 5,000 regulars at Saratoga to General Horatio Gates.[cxxiv] In February 1778, Louis XVI entered alliance with the Colonies, followed by Spain in 1779.

The Naval situation for Britain now became critical. In 1778 the Royal Navy possessed 117 ships of the line to France’s 59 and Spain’s 64. By 1779 France could marshal about 80 of the line.[cxxv] With 63 of the line massed in the channel, against only 57 for the Royal Navy, the combined Continental force blockaded Plymouth and threatened England with invasion.[cxxvi]

Battle of Bunker Hill and Subsequent Campaigns.[cxxvii]

Clinton, who had replaced Howe as C-in-C, now deployed to Savannah as part of Germain’s southern strategy, capturing it in December 1778. Charleston fell in May 1780.[cxxviii] By 1780 the cost of supplying the war in America was consuming £12 million a year (12.5% of the national income).[cxxix]

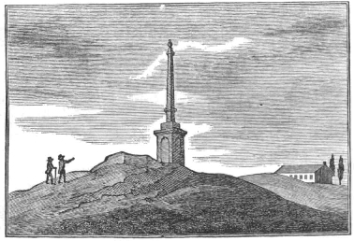

A Tuscan pillar was placed atop Breed’s Hill, to commemorate the spot where Joseph Warren was killed. Seen here in 1818.[cxxx]

Boston bird’s-eye view from the north. J. Bachman, 1877.[cxxxi]

Enlarged Joseph Warren monument of 1842 visible.

Today: the monument on Breed’s hill, with USS Constitution, 44 (1794).[cxxxii]

Notes

[i] Niall Ferguson, Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power (New York: Basic Books, 2004)., p. 71 note

[ii] J. F. C. Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume II: From the Defeat of the Spanish Armada to the Battle of Waterloo, vol. 2, 3 vols. (New York: Da Capo Press, 1955)., p. 272

[iii] http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/shepherd/british_colonies_1763-76.jpg

[iv] Arthur Herman, To Rule the Waves (New York: HarperCollins Publishers Inc., 2004)., p. 306-7

[v] http://www.ushistory.org/declaration/related/sugaract.htm; George Brown Tindall and David E. Shi, American: A Narrative History, 6th ed., vol. 1 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004). p. 193; Ferguson, Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power., p. 72; Herman, To Rule the Waves., p. 307

[vi] Ramsay Muir, A Shorty History of the British Commonwealth, 3rd ed., vol. 2, 2 vols. (London: George Philip & Son, Ltd., 1924)., p. 43

[vii] Herbert Richmond, Statesmen and Sea Power (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1946)., p. 141; Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery (New York: Humanity Books, 1976)., p. 109

[viii] Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume II: From the Defeat of the Spanish Armada to the Battle of Waterloo., p. 272

[ix] Ibid., p. 272

[x] Herman, To Rule the Waves., p. 309

[xi] Tindall and Shi, American: A Narrative History., p. 198

[xii] Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume II: From the Defeat of the Spanish Armada to the Battle of Waterloo., p. 273

[xiii] Alan Taylor, American Colonies: The Settling of North America (New York: Penguin Books, 2001)., p. 306

[xiv] Ibid., p. 308

[xv] Ibid., p. 308

[xvi] Tindall and Shi, American: A Narrative History., p. 193

[xvii] Ferguson, Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power., p. 70

[xviii] Herman, To Rule the Waves., p. 306; Muir, A Shorty History of the British Commonwealth., p. 40

[xix] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Journal_of_Occurrences#/media/File:Boston_1768.jpg

[xx] Ferguson, Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power., p. 72

[xxi] Lawrence James, The Rise and Fall of the British Empire (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Folio Society, 2004)., p. 107

[xxii] Ibid., p. 105

[xxiii] Herman, To Rule the Waves.,, p. 310; Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume II: From the Defeat of the Spanish Armada to the Battle of Waterloo., p. 273

[xxiv] Ferguson, Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power., p. 72 note; Herman, To Rule the Waves.,, p. 311; Muir, A Shorty History of the British Commonwealth., p. 47

[xxv] Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume II: From the Defeat of the Spanish Armada to the Battle of Waterloo., p. 274; Ferguson, Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power., p. 72, says £10,000

[xxvi] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boston_Port_Act

[xxvii] Herman, To Rule the Waves.,, p. 310

[xxviii] Nathaniel Philbrick, Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution (New York: Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 2013)., ebook

[xxix] http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portraitLarge/mw02380/

[xxx] James, The Rise and Fall of the British Empire., p. 109

[xxxi] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Massachusetts_Provincial_Congress

[xxxii] Henry Beebee Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism (New York: A. S. Barnes & Company, 1876)., p. 92

[xxxiii] Herman, To Rule the Waves.,, p. 310-11

[xxxiv] James, The Rise and Fall of the British Empire., p. 110; Tindall and Shi, American: A Narrative History., p. 206

[xxxv] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battles_of_Lexington_and_Concord

[xxxvi] Tindall and Shi, American: A Narrative History., p. 208

[xxxvii] James, The Rise and Fall of the British Empire., p. 111

[xxxviii] John Shy, “Gage, Thomas (1719/20-1787),” The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).; Tindall and Shi, American: A Narrative History., p. 209

[xxxix] James, The Rise and Fall of the British Empire., p. 113

[xl] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battles_of_Lexington_and_Concord#/media/File:Concord_Expedition_and_Patriot_Messengers.jpg

[xli] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_United_States_history#18th_century

[xlii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battles_of_Lexington_and_Concord

[xliii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battles_of_Lexington_and_Concord#/media/File:British_Army_in_Concord_Detail.jpg

[xliv] Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume II: From the Defeat of the Spanish Armada to the Battle of Waterloo., p. 275

[xlv] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Boston

[xlvi] http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/560227.html

[xlvii] Richard Frothingham, “The Battle-Field of Bunker Hill: With A Relation of the Action by William Prescott, and Illustrative Documents” (Massachusetts Historical Society, 1876), http://lcweb2.loc.gov/service/gdc/scd0001/2001/20010131001bh/20010131001bh.pdf.

[xlviii] Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism., p. 84

[xlix] Muir, A Shorty History of the British Commonwealth. p. 53

[l] Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume II: From the Defeat of the Spanish Armada to the Battle of Waterloo., p. 275; Muir, A Shorty History of the British Commonwealth., p. 54

[li] http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portraitLarge/mw78567

[lii] Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism., p. 37; Robert Beatson, Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain, from 1727 to 1783, vol. 4, 6 vols. (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme, 1804)., p. 75

[liii] Frothingham, “The Battle-Field of Bunker Hill: With A Relation of the Action by William Prescott, and Illustrative Documents.”, between p. 4-5

[liv] Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism., Ibid., p. 92

[lv] Tindall and Shi, American: A Narrative History., p. 210

[lvi] Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism., p. 93

[lvii] Ibid., p. 93

[lviii] http://www.nps.gov/bost/learn/historyculture/upload/bh%20roster.pdf

[lix] http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/540561.html

[lx] Frothingham, “The Battle-Field of Bunker Hill: With A Relation of the Action by William Prescott, and Illustrative Documents.”, p. 7

[lxi] Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism., p. 99, 94-5

[lxii] Richard Frothingham, Battle of Bunker Hill (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company., 1890)., p. 13

[lxiii] Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism., p. 95

[lxiv] Ibid., p. 95

[lxv] Frothingham, Battle of Bunker Hill., p. 16

[lxvi] Ibid., p. 17

[lxvii] http://www.loc.gov/resource/g3764b.ar091800/

[lxviii] A. W. H. Pearsall, “Graves, Samuel (1713-1787),” The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

[lxix] Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism., p. 96; see also, Frothingham, Battle of Bunker Hill., p. 23

[lxx] Frothingham, “The Battle-Field of Bunker Hill: With A Relation of the Action by William Prescott, and Illustrative Documents.”, p. 8-9

[lxxi] Beatson, Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain, from 1727 to 1783., p. 76, Ibid., p. 75

[lxxii] Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism., p. 98

[lxxiii] Frothingham, Battle of Bunker Hill., p. 27

[lxxiv] Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism., p. 100

[lxxv] Ibid., p. 100

[lxxvi] Frothingham, Battle of Bunker Hill., p. 26

[lxxvii] http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/540563.html

[lxxviii] Frothingham, Battle of Bunker Hill., p. 29

[lxxix] Charles Francis Adams, “The Battle of Bunker Hill,” The American Historical Review 1, no. 3 (April 1896): 401–13., p. 404, 407

[lxxx] Beatson, Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain, from 1727 to 1783., p. 75

[lxxxi] Ibid., p. 76; on the Spitfire see, T. D. Manning and C. F. Walker, British Warship Names (London: Putnam, 1959). p. 415

[lxxxii] Beatson, Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain, from 1727 to 1783., p. 76

[lxxxiii] http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Bunker_Hill#/media/File:Array_of_American_Forces_on_the_Field_at_the_Battle_of_Breeds_Hill.png

[lxxxiv] Frothingham, “The Battle-Field of Bunker Hill: With A Relation of the Action by William Prescott, and Illustrative Documents.”, p. 9-10

[lxxxv] Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism. , p. 108

[lxxxvi] http://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3g04970/

[lxxxvii] Beatson, Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain, from 1727 to 1783., p. 77

[lxxxviii] Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism., p. 106

[lxxxix] Beatson, Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain, from 1727 to 1783., p. 77

[xc] Frothingham, “The Battle-Field of Bunker Hill: With A Relation of the Action by William Prescott, and Illustrative Documents.”, p. 20

[xci] Philbrick, Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution., Kindle, ebook

[xcii] Beatson, Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain, from 1727 to 1783., p. 77; Frothingham, Battle of Bunker Hill., p. 50-1

[xciii] http://www.loc.gov/item/2006691566/

[xciv] Frothingham, “The Battle-Field of Bunker Hill: With A Relation of the Action by William Prescott, and Illustrative Documents.”, p. 49

[xcv] Frothingham, Battle of Bunker Hill., p. 53

[xcvi] Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism. , p. 107

[xcvii] http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/109476.html

[xcviii] Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism. , p. 107; Frothingham, “The Battle-Field of Bunker Hill: With A Relation of the Action by William Prescott, and Illustrative Documents.”, p. 12

[xcix] http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ea/Bunker_Hill_by_Pyle.jpg

[c] Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism., p. 109

[ci] Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume II: From the Defeat of the Spanish Armada to the Battle of Waterloo., p. 275; Tindall and Shi, American: A Narrative History., p. 211-2; Frothingham, Battle of Bunker Hill., p. 61

[cii] Frothingham, “The Battle-Field of Bunker Hill: With A Relation of the Action by William Prescott, and Illustrative Documents.”, p. 22

[ciii] Ibid., p. 22

[civ] Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism., p. 110

[cv] http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/the-death-of-general-warren-at-the-battle-of-bunkers-hill-17-june-1775-34260

[cvi] Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism.

[cvii] Ibid., p. 103

[cviii] Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume II: From the Defeat of the Spanish Armada to the Battle of Waterloo., p. 275; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Boston; p. 111

[cix] Battle of Bunker Hill, The Boston Patriot, June 17, 1818.

[cx] Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume II: From the Defeat of the Spanish Armada to the Battle of Waterloo., p. 276

[cxi] http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f7/Washington_taking_command_of_the_American_Army_at_Cambridge%2C_1775_-_NARA_-_532874.jpg

[cxii] Philbrick, Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution., Google ebook.; Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: 1775-1781, Historical and Military Criticism., p. 90

[cxiii] Tindall and Shi, American: A Narrative History., p. 212

[cxiv] James, The Rise and Fall of the British Empire., p. 113

[cxv] http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/147

[cxvi] H. H. Brackenridge, The Battle of Bunkers-Hill. A Dramatic Piece, of Five Acts, in Heroic Measure (Philadelphia: Robert Bell, 1776).

[cxvii] http://home.comcast.net/~fredra/SeigeBoston.jpg

[cxviii] Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume II: From the Defeat of the Spanish Armada to the Battle of Waterloo., p. 276

[cxix] N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2006)., p. 334

[cxx] Tindall and Shi, American: A Narrative History., p. 215

[cxxi] Muir, A Shorty History of the British Commonwealth., p. 56; James, The Rise and Fall of the British Empire., p. 118-9

[cxxii] James, The Rise and Fall of the British Empire.,, p. 120

[cxxiii] Ibid., p. 118

[cxxiv] Muir, A Shorty History of the British Commonwealth., p. 58; p. James, The Rise and Fall of the British Empire., p. 121

[cxxv] Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery., p. 110

[cxxvi] Herman, To Rule the Waves., 313

[cxxvii] James, The Rise and Fall of the British Empire., p. 117

[cxxviii] Ibid., p. 121

[cxxix] Herman, To Rule the Waves.,, p. 311; http://www.ukpublicspending.co.uk/year_spending_1778UKmn_14mc1n_30#ukgs302

[cxxx] Frothingham, “The Battle-Field of Bunker Hill: With A Relation of the Action by William Prescott, and Illustrative Documents.”, p. 15

[cxxxi] http://groups.csail.mit.edu/mac/users/rauch/charlestown/maps/19th_Century.html

[cxxxii] http://shamelessenthusiasm.com/2012/09/11/freedom-trail-part-2-hooray-for-freedom/ ; http://www.nps.gov/bost/learn/historyculture/bhm.htm