Infantry Tactics at the Battle of Crecy, 26 August 1346

Introduction

Crecy was the decisive opening battle of the first phase of the Hundred Years War. The campaign that preceded the battle and the perplexing outcome are of unending fascination. This article provides background on the campaign and examines the battle with respect to the crucial question of infantry tactics. The details of the infantry operations at Crecy are significant as Crecy demonstrated both the utility of gunpowder weapons, and the increasing importance of archers and spearmen relative to the traditional European nobility (chivalry).[i]

As Geoffrey Parker explained, “The verdict of battle at Crecy (1346), Poitiers (1356), Agincourt (1415), and countless other lesser encounters confirmed that a charge by heavy cavalry could be stopped by archery volleys.”[ii] Modern, “…explanations for the English dominance have tended to emphasize the importance of the archers’ clothyard shafts fired from prepared positions, on the indiscipline of French armies, and on the inherent superiority of disciplined infantry to cavalry.”[iii] Barbara Tuchman: “England’s advantage lay in combining the use of those excluded from chivalry – the Welsh knifemen, the pikemen, and above all, the trained yeomen who puled the longbow – with the action of the armored knight.”[iv] Or, “The penetration power of the longbow made mail armor essentially useless against the missile weapon.”[v] And again, “The rare efforts when [chivalry] were stupidly committed unsupported by combined arms to a frontal assault against well deployed men fighting on foot generally resulted in disaster for the horsemen.”[vi] Crecy is an excellent case study with which to examine these hypotheses.

Battle of Crecy, 26 August 1346. From a 14th century illustration of Froissart’s Chronicles.[vii]

Background

The battle of Crecy was the result of a complex series of events, but the essential component was the dynastic struggle between the heirs of the Angevin Empire to contest the throne of France. Edward III Plantagenet’s objective was to reverse the expansion of France engineered by Philip II Capetian, the first titled King of France, in the 12th and early 13th centuries.

The Treaty of Paris (1259) concluded the first round of conflict. Henry III and (Saint) Louis IX agreed to a diminished presence of England on French soil.[viii]

Philip II reverses Angevin dominance in France.[ix]

The 14th century iteration of the dynastic struggle involved Philip VI Valois, a successor of the Capetians, and Edward III Plantagenet, the Duke of Aquitaine.[x]

Charles IV, the last Capetian, died without a male heir in 1328. Edward’s mother was Isabella of France, sister of Charles IV. Philip VI was the son of Charles of Valois, himself the son of Philip III (d. 1285) to whom both Philip and Edward were descended (the latter through Philip IV’s daughter, Isabella).[xi]

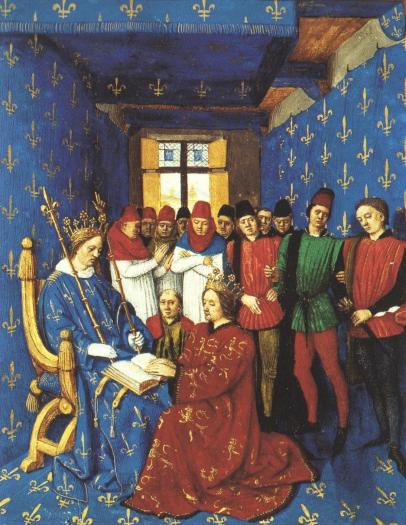

Edward I, King of England and Duke of Aquitaine pays homage to Philip IV, c. 1293. 15th century copy.[xii] Prince Edward (III) repeated this ceremony for Charles IV in 1325;[xiii] a duty for which Edward II made his son the Earl of Aquitaine. Edward III repeated the ceremony for Philip VI at the Amiens cathedral on 6 June 1329.[xiv]

France had gained in strength through alliances with Scotland (1295) and Holland (1328), although the latter’s textile industry remained dependent on English wool, the supply of which was controlled in Flanders by pro-Edward weaver magnate Jacques van Artevelde.[xv] Scotland was diminished by Edward’s campaigns of 1332 and 1333. Through the mediation of Pope Benedict XII, a truce was arranged for 1335.[xvi]

Edward III, King from 29 January 1327, arranged alliances with the Duke of Brabant, the Count of Hainualt and the Count of Gueldros, Guelders, Limburg, Juliers, and Brabant, in addition to the support he received from Emperor Louis IV (Ludwig IV of Bavaria).[xvii]

France in 1314.[xviii]

These developments forced Philip to intervene. First he arranged his alliances: “the king of Bohemia, the duke of Lorraine, the prince-bishop of Liege, the count of Savoy, the count of Saarbrucken, the count of Namur and the count of Geneva.”[xix] Philip began to assemble an invasion fleet in the summer of 1336[xx] and “declared Guienne [Gascony] forfeited” on 24 May 1337.[xxi] Edward was now prepared to accept the title of heir of the Capetians, and thus the throne of France.[xxii] In November 1337 he challenged Philip through the Bishop of Lincoln; although refrained from claiming the throne.[xxiii] Meanwhile French ships attacked and burnt Portsmouth, Portsea, Southampton and with the ships of their Genoese allies, in May 1339, Hastings and Plymouth.[xxiv] On 16 July 1339, Edward , “in a declaration addressed to the pope and cardinals,” claimed the throne of France.[xxv]

The French and English armies are arrayed at Buironfosse where both sides refused battle, in 1339.[xxvi]

In October of the 1339 campaign, Philip, with the army at Peronne, challenged Edward to open battle but was refused.[xxvii] Edward retreated to La Flamengerie, but was confronted by Philip’s army on October 23: Edward took the field, however, neither side engaged. Edward withdrew and arrived in Brussels on 1 November.[xxviii] The pay-off from this campaign was Edward’s announcement on 25 January 1340 of a double monarchy vested in himself as King of both England and France: this released the pro-English Flemish to endorse Edward for the throne of France.[xxix] Following the English naval victory at Sluys, on 24 June 1340, the truce of Esplechin was arranged on 25 September.[xxx]

Edward’s ally, the Duke of Brittany, John III, died in April 1341, resulting in a succession crisis.[xxxi] More campaigns followed, first in Scotland and then the continent, with Edward landing in Brittany in October 1342.

Chateau de Brest, today.[xxxii] The English captured the strategically located fortress of Brest, situated to control the sea-lanes to Gascony, in 1342.[xxxiii] A truce was arranged at Malestroit on 19 January 1343- set to expire in September 1346.[xxxiv]

The Campaign

Failed peace negotiations at Avignon in 1344, compounded by the illiquidity of the Florentine firms bankrolling the English war effort,[xxxv] forced Edward to stake a military claim commensurate to his political claim for the throne of France. War by proxy in Brittany had not achieved the desired aims. In 1346 John of Hainault, along with many of Edward’s other allies, had switched sides or deserted the cause. These political-economic developments placed the English King in a precarious situation.

In June 1344, Parliament advised the King of their hope that “he would make an end to this war, either by battle, or by a suitable peace,”[xxxvi] [xxxvii] Edward’s intention was “to win his rights by force of arms”.[xxxviii] The next year Parliament ordered all landowners to serve or to supply a monetary equivalent of soldiers: “£5 of income from land or rents was to supply an archer, a £10 income supplied a mounted spearman… over £25 supplied a man-at-arms, meaning usually a squire or knight.”[xxxix] “According to the Statute of Winchester of 1258… those with lands or rents worth £2 to £5 per year were, to serve as or provide an archer.”[xl]

Edward III, by William Bruges, c 1430-40.[xli]

The English captured the channel island of Guernsey in the summer of 1345, and thus cleared the route for a landing in Normandy.[xlii] Edward’s strategy for 1346 included several distinct components: an attack from Flanders, combined with or following his own landing in Normandy; the Earl of Northampton’s attack against Brittany; and another operation in Aquitaine.[xliii] Henry of Derby, later Duke of Lancaster, executed the latter, where he campaigned and captured Garonne, the Dordogne, and then defeated French forces at Auberoche in October 1345. Henry also captured La Reole and, significantly, recaptured Aiguillon. In response, the French, under the Duke of Normandy, moved to siege Aiguillon in April 1346.[xliv] Meanwhile, Baron Hugh Hasting, with 250 to 600 archers embarked in 20 ships, executed the Flemish component of the campaign.[xlv]

There was speculation that Edward’s intentions for 1346 were to sail around Brest and land at Bordeaux; thus placed in a position to relieve Aiguillon.[xlvi] It is also conceivable that Edward created rumors of this plan for the purpose of military deception. Others argue that Edward’s clear intention had been the capture of Calais as a permanent base, as had occurred with Brest, and much as Henry V would move to capture Harfleur 70 years later.[xlvii] In the event, the landing in Normandy forced Philip to order the Duke of Normandy, then operating at Aiguillon, to come northward, thus reducing the pressure on the besieged English.[xlviii]

Philip VI of Valois, by Jean de Tillet, 16th Century.[xlix]

For his part, Philip VI was faced with increased English support in Brittany and Flanders. Worse still was the disagreeable prospect of declining battle with Edward for a third time.[l] In the event, bad weather forced a landing in Normandy (where Edward had anyway received promises of support from local nobles).[li]

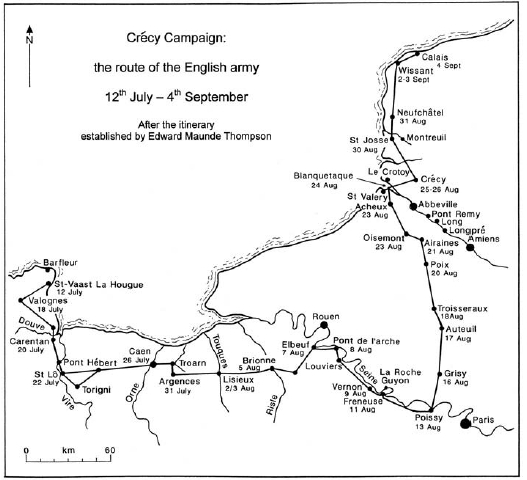

Edward embarked for Normandy on 11 July (Harari: 5 July)[lii] from Portsmouth and arrived at Cotentin on 12 July.[liii] The King landed “on the beach to the south of St Vaast-la-Hogue” in Normandy. Upon landing, the army was composed of 3,200 men-at-arms, 7,800 archers and 2,400 Welsh spearmen.[liv] The subsequent campaign coincided with English naval raids along the coast, in which over 100 enemy ships were destroyed.[lv]

Edward III’s campaign for 1346, July – August.[lvi]

Detail of the campaign.[lvii]

The army took five to six days to marshal once ashore.[lviii] After receiving the endorsement of Godfrey of Harcourt,[lix] Edward marched through Normandy and Picardy, raiding and acquiring booty as he went. Edward’s advancing army defeated the small forces dispatched by Philip to garrison the Norman coast. Philip was caught between a rock and a hard place as his main army of 20,000 men commanded by his son and heir, Jean (Duke of Normandy), was then in Gascony attempting to force the siege of Aiguillon.[lx]

Barfleur was burnt starting on 14 July, the success of which prompted the destruction of Cherbourg shortly afterwards.[lxi] Caen was captured on 26 July.[lxii] These moves seem to support the argument that Edward’s intention was to combine with his Flemish allies before confronting Philip.[lxiii], [lxiv] Edward, however, was placed in a critical situation when the crews of the English fleet mutinied following the capture of Caen, stranding the army without a line of retreat or ready access to his communication with Gascony.[lxv]

Philip’s movements during the campaign are complex: by depriving Edward of battle Philip could reduce him by siege tactics while his own forces grew in strength.[lxvi] Philip took the significant step and issued the nation-wide arriere-ban, or general summons for mobilization.[lxvii] As a result, Philip gathered his army and on 25 July set out for Rouen- where he intended to defend.[lxviii] Edward scouts reported on Philip’s force and movements, with the result that Edward increased the pace of his march east. On 13 August he was at Poissy, where he crossed the Seine after Philip withdrew to Paris, only ten miles away.[lxix] Here Philip dispatched a letter to Edward, challenging him to array his army before Paris in preparation for battle. The English continued to pillage the terrain outside Paris, but moved to withdraw to the north rather than accept battle on Philip’s terms.[lxx]

The forest and village of Crecy, east of the Somme river delta, Abbeville to the south.[lxxi]

Meanwhile, the combined English-Flemish force had arrived at Bethune where a siege was conducted, however, after a series of French counter-attacks, the raiders were forced to withdraw, actually lifting the siege on 24 August: incidentally the same day Duke Jean lifted his siege of Aiguillon to march to Philip’s assistance.[lxxii]

Heading north, Edward crossed the Somme by ford on 22 August, and captured the defenders Philip had situated to block Edward’s route. Harassed by Philip’s vanguard, on 25 August, Edward was prepared to accept battle. He thus moved the army into a defensive position on the hills north of the village of Crecy.[lxxiii] Edward’s position was strong: he was now well supplied by captured victuals from Le Crotoy, and he presently expected the arrival of his Flemish allies under Hugh Hastings (although in fact, the Flemish contingent was retreating without knowledge of Edward’s situation).[lxxiv] Philip rested the army at Abbeville, 14 miles by road from Crecy.[lxxv] The two armies confronted each other on the following day, 26 August 1346.

Modern depiction of English infantry and bowman.[lxxvi]

The Battle

The details of Edward’s army are obscure as the army pay records covering this period no longer exist.[lxxvii].[lxxviii] However, some of the exchequer records concerned with the siege of Calais do exist: they provide concrete figure for Edward’s navy and logistics at that phase of the campaign.[lxxix]

Reconstruction of Edward’s order of battle.[lxxx]

When deployed, the army was composed of 11,000 soldiers in three divisions. The right wing was commanded by Edward the Black Prince, and Prince of Wales. The Prince of Wales’ force consisted of 800 to 1000 dismounted men at arms, 2,000 to 3,000 archers and 1,000 Welsh spearmen.[lxxxi] The Black Prince was supported by a veteran staff, including the Earls of Warwick and Oxford; Count Godfrey d’Harcourt; Sir Thomas Holland, Lord Stafford, Bartholomew Lord Burghersh and Sir John Chandos.[lxxxii]

The second division was commanded by the Earls of Arundel and Northampton, and was composed of 500 men-at-arms and 1,200 to 3,000 archers as well as a quantity of Welsh spearmen.[lxxxiii] In reserve behind these two divisions was Edward III’s division of 700 men-at-arms, 2,000 archers and 1,000 Welsh spearmen.[lxxxiv] Edward’s archers each carried 24 to 48 arrows and were supported by a large reserve, possibly as many as 5 million arrows.[lxxxv] The royal inventory included at least 133,200 arrows; that is to say, at the absolute minimum, more than a hundred thousand arrows had been prepared for the army.[lxxxvi]

Conjectural dispositions at Halidon Hill, 1333.[lxxxvii]

Edward deployed his army in “Halidon-style”- a defensive formation, in reference to the battle of Halidon Hill, 19 July 1333.[lxxxviii] Trenches were dug in front of the army to disrupt the expected French cavalry charge.[lxxxix] Edward III was said to have possessed three “small cannon” at the field- possibly multi-barreled ribauldequins– no surprise considering the revolution in artillery, both field and siege, that had occurred in England during the 13th century.[xc]

Edward III’s army had marched over 300 miles in a single month, but rested on the 25th.[xci]

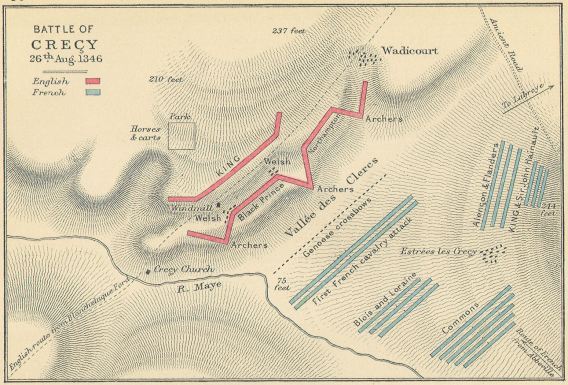

Conventional map of deployments.[xcii]

The size of Philip’s army is largely conjecture. Some estimates place it at 60,000 men; 4,000 to 6,000 Genoese crossbows, and 8,000 to 12,000 cavalry.[xciii] A conservative estimate is a total of 20,000 men, plus between 200 to 2,000 crossbows: twice the size of Edward’s army.[xciv] The first division of cavalry was led by King John of Bohemia (the blind) supported by Philip’s brother, Charles Duke of Alencon, a veteran of the Brittany campaigns. Carlo Grimaldi and Otto Doria commanded the Genoese component.[xcv] Philip’s army was assembled in part by “’lettres de retenue’”- essentially mercenary contracts that pledged the contractor to fight during a certain period of time and for a specified sum.[xcvi] In 1340, six years before Crecy, 28.5% of the royal army was composed of foreign mercenaries.[xcvii] Contingents from Flanders, Picardy, Normandy, Paris, Burgundy and Loire were all present at the battle.[xcviii] The French were tired when they arrived, having marched from Abbeville; whereas the English forces were well rested, fed, and had spent the day preparing.

Infantry Tactics

Philip rose at sunrise and heard mass at St. Peter’s in Abbeville before setting out with the army to confront Edward.[xcix] The army arrived about 4 pm, with the sun setting behind the English.[c] Philip was recommended to delay until the following morning, a suggestion he approved of, but the confusion of the situation, combined with the impatience of the forward ranks of the French army, pushed the battle beyond Philip’s control.

Modern depiction of infantry and Genoese crossbowman.[ci]

At 6 pm it rained.[cii] The exhausted Genoese crossbowmen went into action, as the weather reduced the effectiveness of their weapons. Next, Edward’s longbows, carefully kept dry, developed an intense fire on the Genoese, which may have included fire from Edward’s cannon.[ciii] Both bows and crossbows had been technically prohibited in use between Christian armies since the Second Lateran Council of 1139.[civ] Edward I had incorporated the Welsh longbow into the English army for garrisoning in Scotland: Longbowmen could deliver as many as 10 arrows a minute, out to ranges of 250 to 300 yards, with pull between 80 and 160 lbs.[cv] The bows themselves were made from yew tree (“the most resilient and elastic wood in the world”) imported from Italy through English merchants in Venice.[cvi] The details of period armour versus longbow technology can be read in a number of sources: the essence of the argument is that prior to Crecy, the prevailing tournament-style armour was insufficient.[cvii] The chivalry on both sides were equipped with armour and weapons derived from such sporting occasions: Edward’s royal wardrobe in 1344 included 38 cuirace plates of armour, initially acquired for a tournament held at Windsor in 1278.[cviii]

Site of the battle, today.[cix]

In the event, the hail of longbow fire broke the Genoese attack; the crossbowmen were seriously exposed as their shields were still packed with the baggage train.[cx] The crossbow attack was the prologue to the grand charge of the chivalry. The marshaled chivalry of France were well aware of the “repute and combat records” of their English opposites- from sport, such as jousts and tournaments.[cxi] Indeed, the chivalry of Europe represented an “international knightly community”.[cxii]

Dueling knights: illustration from the Hans Talhoffer manuscript, “Alte Armatur und Ringhunst”, Danish, 1459.[cxiii]

At dusk, with the crossbow attack defeated, the Duke of Alencon (Count d’Alencon), commander of the first division, endorsed by Philip, ordered a general charge against the English right wing- in the process trampling the retreating crossbowmen.[cxiv] The ensuing melee was composed of three distinct French attacks comprising 15 separate charges (reflecting the 15 different contingents of the royal army). On one occasion the English right wing was penetrated and the French infantry possibly captured Edward, the Black Prince.[cxv]

1894 depiction of the battle, showing French cavalry charging English positions.[cxvi]

The French force was unable to break the English line.[cxvii] At nightfall the Count of Hainault led Philip, dismounted twice during these attacks, and wounded, away from battle.[cxviii] As a decade later at Poitiers it is probable that the longbowmen had focused their fire against the lightly armoured horses of the French cavalry.[cxix]

The Battle of San Romano, Paolo Uccello, c. 1438-40, National Gallery London, depicting battle between Florentine and Sienese forces in 1432.[cxx] Note heavily armoured knights and unarmoured horses.

Longbow arrowhead variants.[cxxi]

4,000 French soldiers were killed, including the Duke of Alencon, the Count of Blois, Count Louis Nevers of Flanders, the Count of St. Pol and the Count of Sancerre, Enguerrand de Coucy VI,[cxxii] the Duke of Loraine, the King of Majorca and King John of Bohemia.[cxxiii] The Genoese crossbows were wiped out. The carnage amongst the nobles was immense: for example, ten counts and viscounts, eight barons, one archbishop and one bishop, 80 bannerets and 1,542 knights and squires were all slain by the Black Prince’s division, alone.[cxxiv] Edward is said to have lost 300 men-at-arms and some archers, all told.[cxxv]

Modern depiction of Crecy, showing French cavalry charging through the Genoese crossbow line. Note fieldworks and cannon at English position.[cxxvi] Note also Genoese crossbow shields- not present at the battle.

Outcome: Political – Military

The next day, amidst a thick fog, the Duke of Lorraine arrived on the field with 7,000 infantry, followed by the Count of Savoy with 500 men-at-arms and was routed by the Earl of Warwick and the Earl of Northampton (with 2,000 French losses including the Duke of Lorraine, himself).[cxxvii] All told, English raids involving 500 lances and 2,000 archers killed or captured another 4,000 French soldiers on 27 August.[cxxviii]

Fort Risban today: the site of the original medieval port fortification. Rebuilt in the 17th century and every century subsequently.[cxxix]

The English sieged Calais on 3 September 1346. Early in 1347 Philip was rebuilding his army, however, he was unwilling to take the field. Edward now “ordered the recruitment of 7,200 archers, as well as calling on the services of the Earls of Lancaster, Oxford, Gloucester, Pembroke, Hereford and Devon.”[cxxx] The eleven month siege concluded with Calais’ surrender on 4 August 1347, and was followed shortly thereafter by the ceasefire of 28 September.[cxxxi] Philip VI secured an alliance with Castile and the war was continued at sea through 1349.[cxxxii] It was now that the bubonic plague spread throughout Europe: experts predicted the end of the world.

Philip died in 1350, and was succeeded by King Jean II (1350-1364), against whom the Black Prince continued the war in Aquitaine. Calais, which likely had been Edward III’s objective all along, became the beachhead for the subsequent campaigns of 1355 and 1359-60.[cxxxiii] [cxxxiv] The capture of Brest and Calais provided security for England’s trade, and established defensible outposts on the continent.[cxxxv]

Battle of Poitiers: the Black Prince repeats his father’s tactics; defeats and captures King Jean, 19 September 1356, from Froissart’s chronicle, Louis de Bruges copy, c. 1460.[cxxxvi] Following Crecy, and then the Black Death, in 1351, Jean II introduced reforms designed to improve the discipline of the army.[cxxxvii]

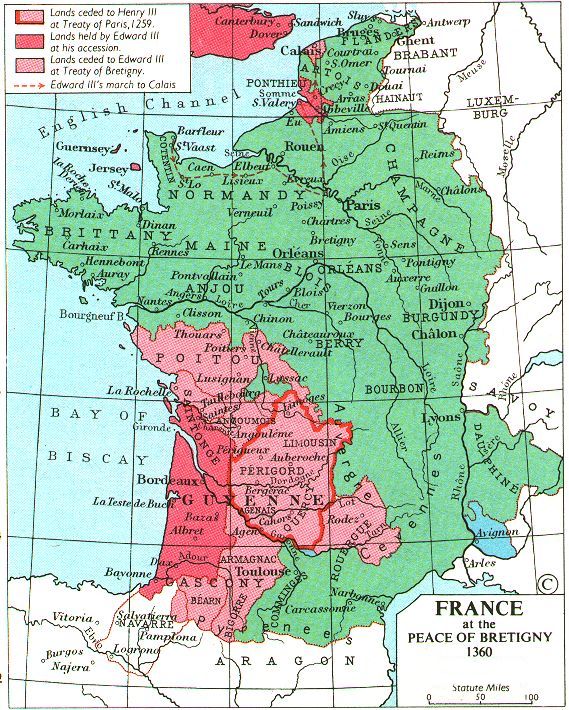

Treaty of Bretigny, 1360. Note also Edward III’s route from Normandy to Calais.[cxxxviii] In addition to territorial concessions, the treaty of Bretigny arranged for the payment of King Jean’s ransom.

Charles V receives Raoul de Presles’ translation (of Augustine’s City of God, 1370), c. 1410.[cxxxix]

Edward’s gains were not to last. The campaigns of Charles V Valois reversed Edward III’s success, resulting in the Treaty of Bruges (1375). When Edward died in 1377, England’s holdings in France had been reduced to the rump of Bordeaux and the fortresses of Calais and Brest- the latter held until 1397.[cxl] Armourers in France, Italy and England, meanwhile, responded to the infantry revolution by improvements to plate armour technology over the half century from 1350 to 1400. The knight could now rely on full-body plate to generally protect against the longbow.[cxli] Ultimately, English reliance on the longbow was a weakness: skilled bowmen could not be trained in the numbers required for the ongoing campaigns in France. Gunpowder, the great leveler, was set to revolutionize European warfare.[cxlii] The groundwork was prepared for the second phase of the Hundred Years War.

France in 1400.[cxliii]

[i] John France, Perilous Glory, The Rise of Western Military Power (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011)., p. 153

[ii] Geoffrey Parker, The Military Revolution, Military Innovation and the Rise of the West, 1500 – 1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011)., p. 69

[iii] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”,, p. 337 74n

[iv] Barbara W. Tuchman, A Distant Mirror, The Calamitous 14th Century (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978)., p. 88

[v] John J. Mortimer, “Tactics, Strategy, and Battlefield Formation During the Hundred Years War: The Role of the Longbow in the ‘Infantry Revolution’” (MA Thesis, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, 2013)., p. 8

[vi] Bernard S Bachrach, review of Weapons and Warfare in Renaissance Europe: Gunpowder, Technology, and Tactics, by Bret S. Hall, Canadian Journal of History 33, no. 1 (1998): 94., p. 95

[vii] http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Battle_of_crecy_froissart.jpg

[viii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Paris_%281259%29

[ix] http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/12/Territorial_Conquests_of_Philip_II_of_France.png

[x] J. F. C. Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume I: From the Earliest Times to the Battle of Lepanto, vol. 1, 2 vols. (New York: Da Capo Press, 1987)., p. 445

[xi] Ibid., p. 444

[xii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hommage_of_Edward_I_to_Philippe_le_Bel.jpg

[xiii] Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume I: From the Earliest Times to the Battle of Lepanto., p. 444

[xiv] Ibid., p. 445

[xv] Ibid., p. 446, 450

[xvi] Ibid., p. 448

[xvii] Jaliker14, “History – Edward III & The Hundred Years War,” Study notes, Pret-A-Revise, (November 17, 2014), http://pret-a-revise.com/2014/11/17/history-edward-iii-the-hundred-years-war/. ; Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume I: From the Earliest Times to the Battle of Lepanto., p. 448-9

[xviii] http://www.westpoint.edu/history/SiteAssets/SitePages/Dawn%20Of%20Modern%20Warfare/france_1314.gif

[xix] Bertrand Schnerb, “Vassals, Allies and Mercenaries: The French Army before and after 1346,” in The Battle of Crecy, 1346, ed. Andrew Ayton and Philip Preston, Warfare in History (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2007), 265–72., p. 268

[xx] N. A. M. Rodger, The Safeguard of the Sea. A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1998)., p. 446

[xxi] Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume I: From the Earliest Times to the Battle of Lepanto.,, p. 448

[xxii] Rodger, The Safeguard of the Sea. A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649., p. 446; Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume I: From the Earliest Times to the Battle of Lepanto., p. 445

[xxiii] Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume I: From the Earliest Times to the Battle of Lepanto., p. 448

[xxiv] Ibid., p. 450; Rodger, The Safeguard of the Sea. A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649., p. 446

[xxv] Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume I: From the Earliest Times to the Battle of Lepanto., p. 450

[xxvi] http://www.maisonstclaire.org/common/mss_images/chronicles/BNF_FR76_chroniques_d_angleterre/02-Bataille%20de%20Buironfosse%20(1339).jpg

[xxvii] Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume I: From the Earliest Times to the Battle of Lepanto., p. 450

[xxviii] Ibid., p. 451

[xxix] Ibid., p. 451

[xxx] Rodger, The Safeguard of the Sea. A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649., p. 447

[xxxi] Ibid., p. 447

[xxxii] https://cedpics.files.wordpress.com/2009/01/p1010679.jpg

[xxxiii] Rodger, The Safeguard of the Sea. A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649., p. 102

[xxxiv] Ibid., p. 447; Robin Neillands, The Hundred Years War (Routledge, 2002)., p. 90

[xxxv] Tuchman, A Distant Mirror, The Calamitous 14th Century., p. 81

[xxxvi] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 315

[xxxvii] Ibid., p. 321

[xxxviii] Ibid., p. 348

[xxxix] Tuchman, A Distant Mirror, The Calamitous 14th Century., p. 82

[xl] Mortimer, “Tactics, Strategy, and Battlefield Formation During the Hundred Years War: The Role of the Longbow in the ‘Infantry Revolution.’”, p. 32-3

[xli] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_III_of_England#mediaviewer/File:Edward_III_of_England_(Order_of_the_Garter).jpg

[xlii] Rodger, The Safeguard of the Sea. A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649., p. 102

[xliii] Neillands, The Hundred Years War., p. 90

[xliv] Rodger, The Safeguard of the Sea. A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649., p. 448

[xlv] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 325; Yuval Noah Harari, “Inter-Frontal Cooperation in the Fourteenth Century and Edward III’s 1346 Campaign,” War in History 6, no. 4 (1999): 379–95., p. 384

[xlvi] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 317

[xlvii] Ibid., p, 339, Jan Willem Honig, “Reappraising Late Medieval Strategy: The Example of the 1415 Agincourt Campaign,” War in History 19, no. 2 (2012): 123–51.

[xlviii] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 376

[xlix] http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Philippe_VI_de_Valois.jpg

[l] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”,, p. 327-9

[li] Ibid.,, p. 322

[lii] Harari, “Inter-Frontal Cooperation in the Fourteenth Century and Edward III’s 1346 Campaign.”, p. 381

[liii] Rodger, The Safeguard of the Sea. A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649., p. 102-3

[liv] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 308

[lv] Rodger, The Safeguard of the Sea. A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649., p. 103

[lvi] http://www.emersonkent.com/images/hundred_years_war.jpg

[lvii] Map 1, Andrew Ayton and Philip Preston, The Battle of Crecy, 1346, Warfare in History (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2007).,p. 2

[lviii] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 311

[lix] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 343

[lx] Harari, “Inter-Frontal Cooperation in the Fourteenth Century and Edward III’s 1346 Campaign.”, p. 384

[lxi] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 344

[lxii] Christopher Rothero, The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers, Men-At-Arms Series (Hong Kong: Reed International Books Ltd., 1995)., p. 5

[lxiii] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 334

[lxiv] Ibid., p. 364

[lxv] Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume I: From the Earliest Times to the Battle of Lepanto., p. 460; Harari, “Inter-Frontal Cooperation in the Fourteenth Century and Edward III’s 1346 Campaign.”, p. 383

[lxvi] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 339

[lxvii] Tuchman, A Distant Mirror, The Calamitous 14th Century., p. 83; , p. 267

[lxviii] Rothero, The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers., p. 5

[lxix] Ayton and Preston, The Battle of Crecy, 1346., p. 2

[lxx] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 372-3

[lxxi] google earth

[lxxii] Harari, “Inter-Frontal Cooperation in the Fourteenth Century and Edward III’s 1346 Campaign.”, p. 385

[lxxiii] Rothero, The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers., p. 5-6

[lxxiv] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 383; Harari, “Inter-Frontal Cooperation in the Fourteenth Century and Edward III’s 1346 Campaign.”, p. 391

[lxxv] Rothero, The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers., p. 7

[lxxvi] Ibid., p. 26

[lxxvii] Craig Lambert, “Edward III’s Siege of Calais: A Reppraisal,” Journal of Medieval History 37, no. 3 (2011): 245–56., p. 2

[lxxviii] Ibid., p. 247 fn; see also, Andrew Ayton, “The English Army at Crecy,” in The Battle of Crecy, 1346, ed. Andrew Ayton and Philip Preston, Warfare in History (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2007), 159–252., p. 246

[lxxix] Susan Rose, “The Wall of England, to 1500,” in The Oxford Illustrated History of the Royal Navy, ed. J. R. Hill and Bryan Ranft (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 1–23., p. 10

[lxxx] Ayton, “The English Army at Crecy.”, p. 242-4. Appendix 2

[lxxxi] Rothero, The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers., p. 7

[lxxxii] Ibid., p. 7

[lxxxiii] Ibid., p. 7

[lxxxiv] Charles W. C. Oman, The Art of War in the Middle Ages, ed. John H. Beeler (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1968)., p. 127-8

[lxxxv] France, Perilous Glory, The Rise of Western Military Power., p. 153

[lxxxvi] Michael Prestwich, “The Battle of Crecy,” in The Battle of Crecy, 1346, ed. Andrew Ayton and Philip Preston, Warfare in History (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2007), 139–58., p. 153

[lxxxvii] Mortimer, “Tactics, Strategy, and Battlefield Formation During the Hundred Years War: The Role of the Longbow in the ‘Infantry Revolution.’”, p. 41, Figure 2

[lxxxviii] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 339; Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume I: From the Earliest Times to the Battle of Lepanto., p. 451

[lxxxix] Rothero, The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers., p. 7

[xc] Tuchman, A Distant Mirror, The Calamitous 14th Century., p. 71; David Stewart Bachrach, “English Artillery 1189-1307: The Implications of Terminology,” The English Historical Review 121, no. 494 (December 2006): 1408–30. p. 1430; Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume I: From the Earliest Times to the Battle of Lepanto., p. 464 fn

[xci] Rothero, The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers., p. 6

[xcii] http://historywarsweapons.com/wp-content/uploads/image/Crecy2.jpg

[xciii] Rothero, The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers., p. 7; Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 383 fn

[xciv] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 371

[xcv] Rothero, The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers., p. 9

[xcvi] Schnerb, “Vassals, Allies and Mercenaries: The French Army before and after 1346.”, p. 267

[xcvii] Ibid., p. 268

[xcviii] Ibid., p. 268

[xcix] http://www.maisonstclaire.org/resources/chronicles/froissart/book_1/ch_126-150/fc_b1_chap128.html

[c] Tuchman, A Distant Mirror, The Calamitous 14th Century., p. 70; John Keegan, The Face of Battle, A Study of Agincourt, Waterloo and The Somme (Penguin Books, 1978)., p. 87

[ci] Rothero, The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers.,, p. 33

[cii] Fuller, A Military History of the Western World. Volume I: From the Earliest Times to the Battle of Lepanto., p. 465

[ciii] Rothero, The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers., p. 9

[civ] Rory Cox, “Asymmetric Warfare and Military Conduct in the Middle Ages,” Journal of Medieval History 38, no. 1 (March 2012): 100–125., p. 105

[cv] Tuchman, A Distant Mirror, The Calamitous 14th Century., p. 70; Keegan, The Face of Battle, A Study of Agincourt, Waterloo and The Somme., p. 84 ; Mortimer says 400 yards, although really effective at half that. Mortimer, “Tactics, Strategy, and Battlefield Formation During the Hundred Years War: The Role of the Longbow in the ‘Infantry Revolution.’” p. 6, 26

[cvi] Mortimer, “Tactics, Strategy, and Battlefield Formation During the Hundred Years War: The Role of the Longbow in the ‘Infantry Revolution.’”, p. 24-5

[cvii] Ibid., Keegan, The Face of Battle, A Study of Agincourt, Waterloo and The Somme., Thom Richardson, “Armour in England, 1325-99,” Journal of Medieval History 37 (2011): 304–20.

[cviii] Richardson, “Armour in England, 1325-99.”, p. 314

[cix] http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Crecy-en-Ponthieu_champ-de-bataille.jpg

[cx] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 386

[cxi] Tuchman, A Distant Mirror, The Calamitous 14th Century., p. 70; Keegan, The Face of Battle, A Study of Agincourt, Waterloo and The Somme., p. 87

[cxii] Ayton and Preston, The Battle of Crecy, 1346., p. 5

[cxiii] http://www.kb.dk/da/nb/materialer/haandskrifter/HA/e-mss/thalhofer/thott-2_290.html ; http://www.aemma.org/onlineResources/talhoffer1459/contents_body.htm

[cxiv] Rothero, The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers., p. 9; Tuchman, A Distant Mirror, The Calamitous 14th Century. p. 87

[cxv] Rothero, The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers., p. 9

[cxvi] http://www.antiquaprintgallery.com/militaria-cavalry-v-archers-battle-of-crecy-1894-135735-p.asp

[cxvii] Oman, The Art of War in the Middle Ages., p. 129

[cxviii] Rothero, The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers., p. 9-10; Tuchman, A Distant Mirror, The Calamitous 14th Century. p. 88

[cxix] Tuchman, A Distant Mirror, The Calamitous 14th Century., p. 148-9

[cxx] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Battle_of_San_Romano#mediaviewer/File:San_Romano_Battle_(Paolo_Uccello,_London)_01.jpg

[cxxi] Mortimer, “Tactics, Strategy, and Battlefield Formation During the Hundred Years War: The Role of the Longbow in the ‘Infantry Revolution.’”, p. 32, figure 1.

[cxxii] “perhaps” – Tuchman, A Distant Mirror, The Calamitous 14th Century., p. 88

[cxxiii] Rothero, The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers., p. 10

[cxxiv] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 388

[cxxv] Ibid., p. 389

[cxxvi] http://photos1.blogger.com/blogger/3908/963/1600/bataille%20de%20crecy%201346.jpg

[cxxvii] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 389-90; Schnerb, “Vassals, Allies and Mercenaries: The French Army before and after 1346.”, p. 269

[cxxviii] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 390; http://www.maisonstclaire.org/resources/chronicles/froissart/book_1/ch_126-150/fc_b1_chap130.html

[cxxix] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Risban

[cxxx] Lambert, “Edward III’s Siege of Calais: A Reppraisal.”, p. 249

[cxxxi] Rodger, The Safeguard of the Sea. A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649., p. 103

[cxxxii] Ibid., p. 104

[cxxxiii] Rogers, “‘Werre Cruelle and Sharpe’: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327 – 1347.”, p. 358-9

[cxxxiv] Harari, “Inter-Frontal Cooperation in the Fourteenth Century and Edward III’s 1346 Campaign.”, p. 389

[cxxxv] Rodger, The Safeguard of the Sea. A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649., p. 104

[cxxxvi] http://images.easyart.com/highres_images/easyart/3/0/301947.jpg; Tuchman, A Distant Mirror, The Calamitous 14th Century., p. 234, plate 4.

[cxxxvii] Ibid., p. 128

[cxxxviii] http://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/maps/1360france.jpg

[cxxxix] http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Raoul_de_Presles_presents_his_translation_to_Charles_V_of_France.jpg

[cxl] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brest,_France#History

[cxli] Keegan, The Face of Battle, A Study of Agincourt, Waterloo and The Somme., p. 87; Mortimer, “Tactics, Strategy, and Battlefield Formation During the Hundred Years War: The Role of the Longbow in the ‘Infantry Revolution.’”, p. 2; Richardson, “Armour in England, 1325-99.” , p. 315

[cxlii] Mortimer, “Tactics, Strategy, and Battlefield Formation During the Hundred Years War: The Role of the Longbow in the ‘Infantry Revolution.’”, p. 7

![militaria-cavalry-v-archers.-battle-of-crecy.-1894-wdjb--135735-p[ekm]400x243[ekm]](https://airspacehistorian.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/militaria-cavalry-v-archers-battle-of-crecy-1894-wdjb-135735-pekm400x243ekm.jpg?w=920)