Operation Anaconda: Victory and Defeat in Afghanistan, March 2002

Operation Anaconda was the largest NATO combat operation since the Bosnian War of 1992-5, and the most complex Special Operations Forces (SOF) mission the United States has ever engaged in, dwarfing smaller but more high profile events such as the Battle for Tora Bora in December 2001 or the Battle of Mogadishu during Operation Gothic Serpent in October 1993.

Defeating the Taliban in Afghanistan would be a hugely complicated multi-domain operation conducted by Central Command (CENTCOM) the American military’s Unified Command responsible for the Middle East. What became known as Operation Enduring Freedom began only days after the September 11 attacks in 2001, the first component of which – involving CIA cash injections and Special Forces deployments – was codenamed Jawbreaker.

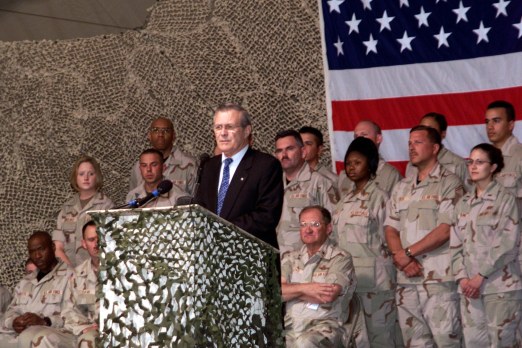

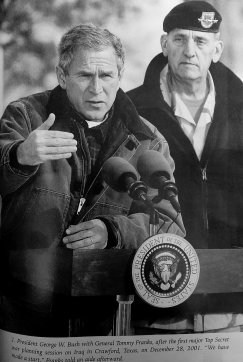

A pinprick in the now 19 year long war in Afghanistan, Operation Anaconda, 2 – 19 March 2002, was nevertheless the largest operation of the initial phase of the war. Today the operation has the reputation of a debacle, the result of flawed planning and joint cooperation.[1] Donald Wright, on the other hand, described Anaconda as “an overall success” and General Tommy Franks stated in his memoirs that the operation resulted in “winning a decisive battle”.[2]

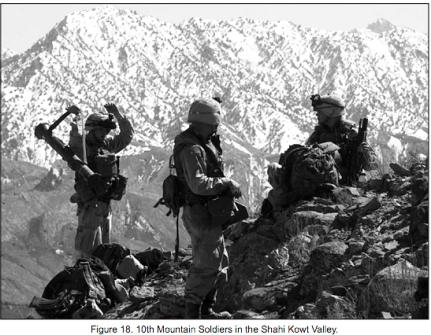

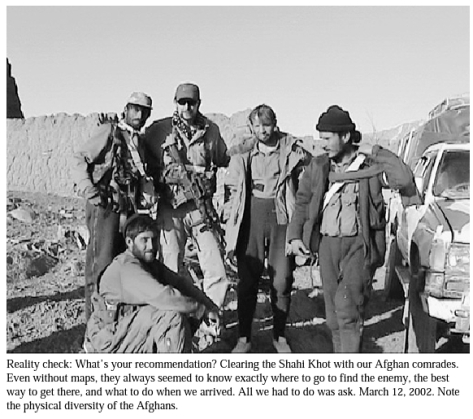

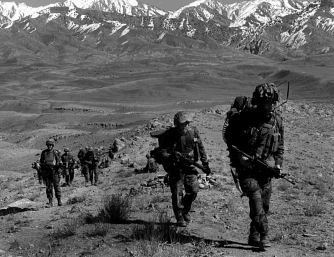

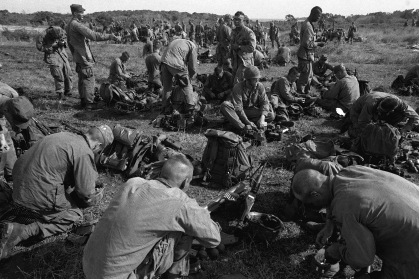

10th Mountain Division soldiers in the Shahi Khot valley, from Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War

The two week-long battle for control of the Shahi Khot valley was the point at which, in the military sense, the coalition won the war in Afghanistan. The CIA had correctly identified a major enemy stronghold, and almost the entirety of the coalition forces in Afghanistan were employed to destroy it, demonstrating that not only American SOF and Special Forces, but also multinational conventional forces, could engage and destroy hardened al Qaida fighters on their home ground. The battle was the culmination of an operational concept meant to correct the errors of Tora Bora, by denying the mujahideen in the Shahi Khot the ability to escape.[3]

This post provides the background to Operation Enduring Freedom, and the essential battle narrative of Operation Anaconda, to give the reader the information needed to decide for themselves if the battle, and the war in Afghanistan, had by the end of March 2002 been a success or failure.

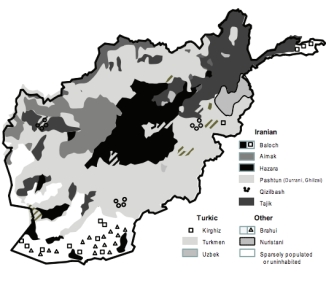

Ethnicities map of Afghanistan, from Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War, (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2010) & 1997 Ethnolinguistic map

Background: Enduring Freedom

The goal of Operation Enduring Freedom was to liberate Afghanistan, a mountainous Texas-sized country bordering on Iran, Pakistan, and the former Soviet Republics of Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. Reflecting the multi-faceted nature of the Global War on Terror, a key objective of Operation Enduring Freedom would be to defeat and destroy al Qaida terrorists inside the country. Operational planning for the invasion began in the weeks immediately following the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington DC, and commenced with the insertion of the first CIA and SOCOM guerillas under codename Jawbreaker on 19 September, the day Bush later chose to designate as the beginning of combat operations in Afghanistan. The president had authorized CIA action against terrorists world-wide, beginning with Afghanistan, two days prior.[4]

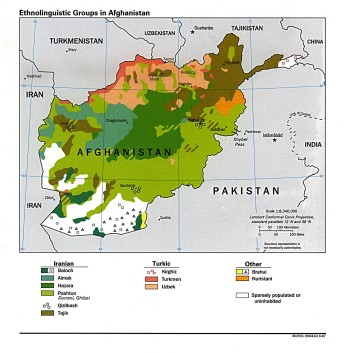

Pashtun belt and ring road, from Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War

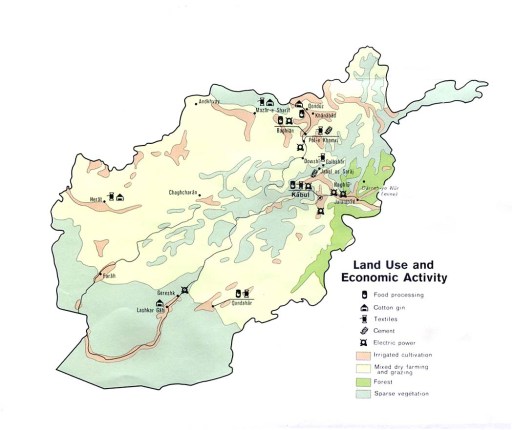

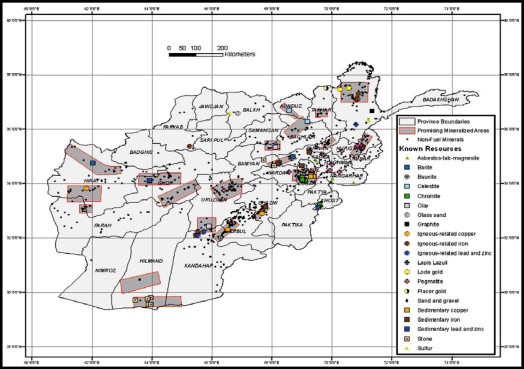

1972 economic map of Afghanistan, showing the largely pastoral and agrarian nature of the country, textiles representing the only major industrial activity

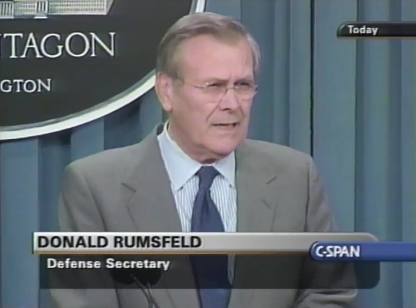

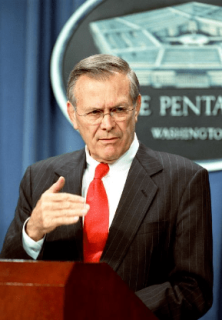

The operation that developed was in fact a showcase of the new military concept of “transformation” that was a key goal of Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. On 20 September during a Pentagon press briefing, Rumsfeld told reporters that the campaign “we’re engaged in is very, very different from World War II, Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf War, Kosovo, Bosnia…”.[5] On 4 October President Bush announced humanitarian aid for Afghanistan, stating in his remarks that, “this is a unique type or war. It’s a war that is going to require building a broad coalition of nations who will contribute, one way or the other, to make sure that we all win.”[6] On 1 November National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice reinforced these sentiments, stating, “this may be one year, it may be several years, it may be more than one administration…. This is going to take some time.”[7]

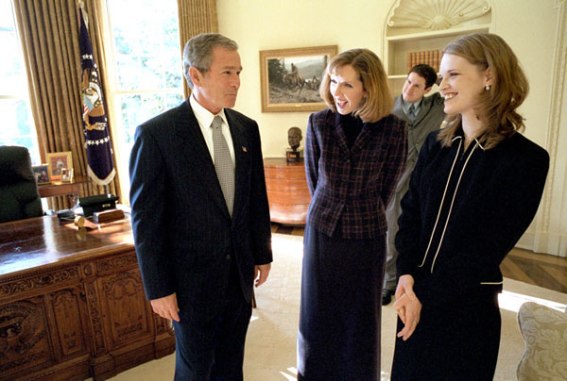

President Bush speaking to Chief of Staff Andy Card and National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, 12 September 2001,photograph by Eric Draper & President George W. Bush in the Oval Office with Vice President Dick Cheney, White House Chief of Staff Andrew Card, and National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, 20 September 2001

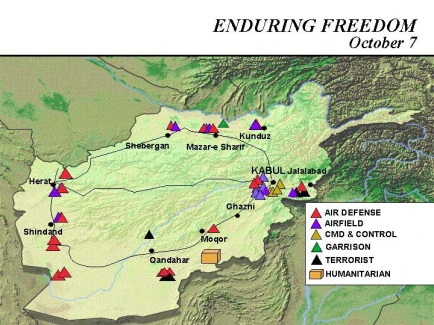

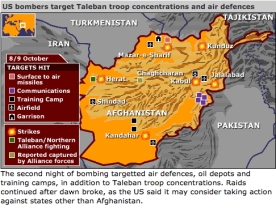

On 7 October under the CENTCOM leadership of General Tommy Franks, Operation Enduring Freedom officially commenced. Within a matter of days there were 110 CIA officers and 316 Special Forces operators in country.[8] On 17 October President Bush told the assembled USAF air personnel at Travis Air Force Base, California, that, “you’re among the first to be deployed in America’s new war against terror and against evil, and I want you to know, America is proud – proud of your deeds, proud of your talents, proud of your service to our country.”[9] By 19 November Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld was praising the special operators in Afghanistan, noting that just the day before, the coalition had flown 138 combat sorties and air dropped 39,240 daily rations.[10]

20 September 2001, USAF stages assets for Operation Enduring Freedom, Washington Post archive

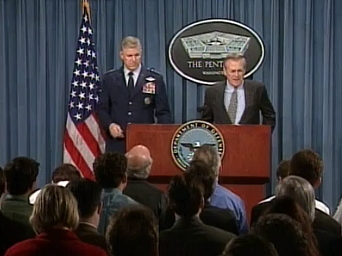

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), USAF General Richard B. Myers and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld giving a press conference on 9 October 2001., TSGT Jim Varhegyi collection. As early as 18 September Rumsfeld had stated that the War on Terror would require that the US “drain the swamp” the terrorists lived in, referring to the countries harbouring them, and that this effort would require “a distinctly different approach from any war that we have fought before.” On 7 October Rumsfeld and Meyers briefed the press at the Pentagon, announcing air and missile strikes against the Taliban, attacks by 15 bombers (including B2 stealth bombers), 25 naval aircraft, and 50 tomahawk missiles fired from USN and Royal Navy ships and submarines.

Coalition airbases at the outset of Operation Enduring Freedom, from Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War, & 7 October 2001, RAF, RN and USN, USAF airstrikes wipe out Afghanistan’s air defences.

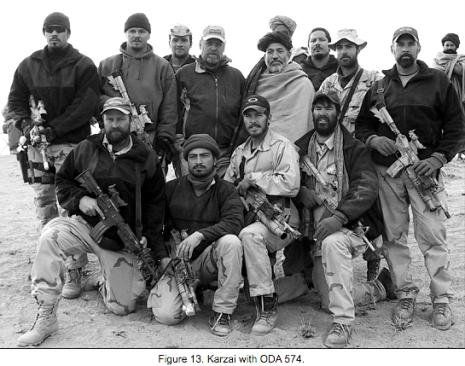

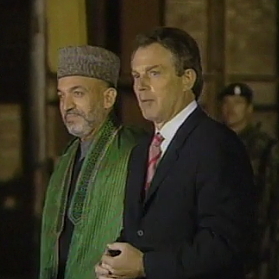

Within sixty days the most immediate stages of the mission were complete: both Afghanistan’s capital, Kabul, and its second largest city, Kandahar, had fallen to the US-led NATO coalition and the Afghan Northern Alliance (United Front), their fast moving teams of 5th Special Forces Group (SFG) green berets utilizing the coalition’s fearsome airpower to pulverize any opposition.[11] The combination of air support, air supply, and special forces on a large scale enabled a string of victories that effectively put the coalition in control of Afghanistan, and made possible Hamid Karzai’s elevation to head of the interim government, formalized by the UN’s Bonn Agreement of 5 December 2001.

18 October 2001, C-17A Globemasters launch from Naval Air Stations (NAS) Sigonella, Italy, in support of Operation Enduring Freedom, Staff Sergeant Ken Bergmann, USAF collection

Karzai was soon inaugurated as Chairman of the interim Governing Council, and just short of three years to the day later he was inaugurated as President under the newly promulgated Afghan constitution.[12] Parliamentary elections were at that time scheduled for the spring of 2005. On 7 November 2001 National Security Advisor Dr. Rice stated, “we are trying very hard to send the message this can’t be a made-in-America solution. This is something that the Afghans themselves are going to have to take on. And I think we are agnostic as to the form that takes… I think we will leave [it] at this point to the UN and to the members of the Afghan community who are trying to get it done.”[13] When Defense Secretary Rumsfeld visited Bagram Air Base on 16 December and met with President Karzai, one of the interim chairman’s aides applauded Rumsfeld’s approach: “The United States has done very well so far… The (American servicemen) who serve with our forces know our culture and respect it… You (are) doing this right,” said the aide favourably of the American effort, in contrast to the heavy-handed Soviet invasion of 1979.[14]

Hamid Karzai posing with ODA 574, one of the 5th Special Forces Group (SFG) teams that acted as the spearhead for the Northern Alliance, from Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War

Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and General Tommy Franks taking questions during a Pentagon press briefing, 15 November 2001 & on 6 December Rumsfeld reiterated that the Taliban and al Qaida leadership would be brought to justice.

Tora Bora

On 13 November, as the Northern Alliance approached Kabul, the remaining Taliban forces, including bin Laden with the other al Qaida leadership, withdrew with between 700, 1,500 or possibly as many as 3,000 fighters, to Jalalabad, fifty miles from the Pakistan border, and then to their stronghold cave complex in Nangarhar province, the location of Tora Bora in the White Mountains that overlooked the Khyber Pass gateway into Pakistan.[15]

Battle of Tora Bora, from Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War. Unlike the initial two months when 5th SFG green berets had taken charge, the assault on bin Laden’s compound was primarily a JSOC operation.

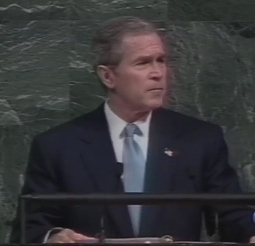

The Taliban had long been supported by Pakistan’s Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI), who had used Kunduz in the north as a base for training fighters inside Afghanistan. But with the Taliban on the run the Pakistani forces in Afghanistan made a quick departure and President Musharraf promised to work with the coalition to secure the border, although how seriously he took this request is certainly debatable.[16] Musharraf had visited New York on 8 November for the UN General Assembly meeting, where he met with Bush who was grateful for the diplomatic efforts Musharraf had undertaken with Indian Prime Minister Vajpayee. Bush gave his UN address on 10 November, describing the terrorist attacks on September 11 in graphic Straussian terms, a Huntingtonesque international tragedy with the potential to culminate in Tom Clancy-like sum of all fears WMD attack, and demanding justice for the attacks.[17]

HMMWVS deploying “at a forward operating location” from C-17, 20 November 2001, Technical Sergeant Scott Reed, USAF collection & Navy SEALs disembarking from an MC-130E Combat Talon, 16th Special Operations Wing, 22 November 2001, TSGT Scott Reed.

In evidence of the United States’ resolve Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) attempted to infiltrate and capture bin Laden at Tora Bora.[18] This was the largest offensive of the war so far, with NATO and the Northern Alliance successfully clearing Tora Bora between 6 and 17 December.[19] This time the attack was spearheaded by Task Force Dagger, the Delta Force element, and the newly arrived Task Force K-Bar, Navy SEALs and 3rd SFG.[20] These SOCOM forces would enable three Afghan warlords of various competency, Hazarat Ali, Haji Zaman Gamsharik, and Hajji Zahir, to mass and deploy 2,000 fighters, combined with JSOC’s 40 Delta operators, 14 Green Berets, six CIA operatives (who had knowledge of the caves derived from their efforts aiding the mujahideen against the Soviets),[21] a handful of Air Force controllers, and 12 British SBS commandos.

2,000 lb Mk84 bombs converted to Joint Direct Attack Munitions (JDAMs), loaded aboard the rotary launcher on a B-1B Lancer, 5 November 2001, Staff Sergeant Larry A. Simmons collection. & MV MAJ. Bernard F. Fisher unloading JDAMs on 26 October 2001, Staff Sergeant Shane Cuomo, USAF collection

JDAMs being loaded aboard B-1B bombers from the 28th Air Expeditionary Wing, 13 November 2001 & 28th Air Expeditionary Wing loading JDAMs onto B-52s, 28 November 2001, both from the collection of Staff Sergeant Shane Cuomo.

The coalition dropped 1,110 JDAMs and other precision munitions (not to mention 15,000 lb daisy cutters) on the mountain caves but, despite the overwhelming firepower, Bin Laden, Ayman al-Zawahiri, and Mohammed Atef, all escaped by fleeing into Pakistan while Taliban leader Mullah Omar went into hiding in the mountainous south-east of the country.[22] Elsewhere, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed fled into Pakistan until captured in March 2003. General Franks, at the time of Tora Bora, had believed that Pakistan would be more diligent in terms of preventing al Qaida from crossing into its territory, and that the Northern Alliance was more united than was in fact the case.[23] Furthermore, Franks himself was under pressure from the DOD and White House to wrap up the war in Afghanistan and deliver a viable Iraq war plan. Franks’ frustration with pacing had gotten to the point where the CENTCOM commander was contemplating intervening directly above Lt. General Paul Mikolashek of Third Army, who, based at Camp Doha, Kuwait, was ostensibly in charge of operations in Afghanistan.[24]

Villagers watch B-52 strikes on 9 December 2001 during the Battle of Tora Bora (6 – 17 December).

Delta Force AFO coordinator Lt. Colonel Pete Blaber (right) author of The Mission, The Men, and Me (2008), with Major Jim “Jimmy” Reese, at the grave of renowned Afghan commander Ahmed Shah Massoud – assassinated by the Taliban on 9 September 2001.

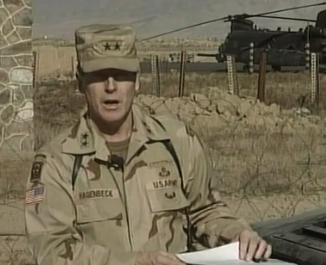

Although the propaganda impact of bin Laden’s escape from Tora Bora was immense, the strategic situation had changed little: CENTCOM was moving into Phase IV after the New Year, which meant deploying conventional US Army forces to assist with stability operations.[25] The next phase of operations would require a dramatic expansion in air lift, housing and logistics which Franks knew would impose a serious delay on the tempo of operations.[26] Moving to Phase IV was therefore an extremely difficult and escalatory action that would require several weeks to prepare, involving the deployment of conventional US Army assets from the US 10th Mountain Division (CO, Major General Franklin Hagenbeck), and the 101st Airborne Division.

Major General Hagenbeck and the 10th Mountain’s divisional HQ had arrived at the K2 airbase in Uzbekistan on 12 December, at which point it became the campaign’s Combined Land Component Command (CFLCC), represented by Lt. General Paul Mikolashek, US Third Army.[27] The command situation within Afghanistan was complex, all the cooperation between Special Forces and the Afghan warlords now conducted by Joint Special Operations Task Force-North (JSOTF-N), based at K2, and Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force-South (CJSOTF-S, CO Captain Robert Harward), established in December 2001 at Kandahar.

UN Beechcraft B200 flying in to Mazir-e Sharif, 13 December 2001, Staff Sergeant Cecilio Ricardo, USAF collection

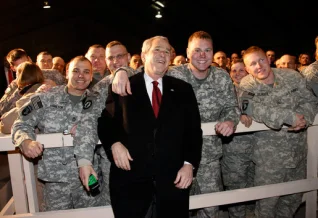

Colonel John Mulholland, US Army, CO 5th SFG, and soldiers from the USAF and 10th Mountain Division, meeting with Donald Rumsfeld on 16 December 2001 at Bagram Air Base, Helene C. Stikkel collection. In addition to visiting the troops at Bagram, Rumsfeld met with international and Afghan press.

General Dostum’s Northern Alliance troops after capturing Mazar-e Sharif, 15 December 2001, Staff Sergeant Cecilio Ricardo, USAF collection

But already the war seemed over, and by 25 January Hagenbeck and Mikolashek were contemplating measures for drawing down.[28] The military mission to liberate Afghanistan had already been achieved within the first hundred days, with humanitarian missions and demobilization now the foremost goal under international leadership. As early as 28 November UN Secretary General Kofi Annan had raised the issue of the estimated 6 – 7.5 million refugees fleeing Afghanistan, an issue President Bush agreed was of major concern.[29]

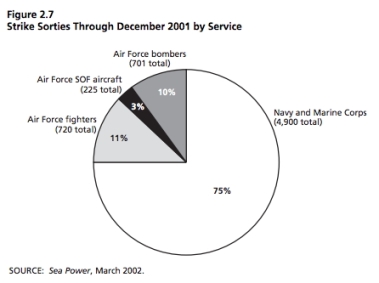

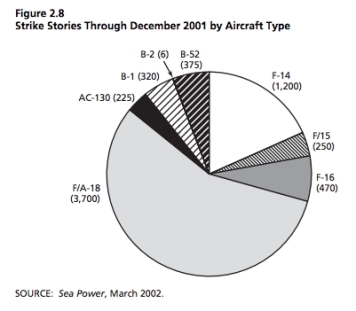

By December humanitarian assistance to the tune of 127,368 tons of food (the USAF air dropped 2,423,700 ration packets), had been delivered. On the military front the NATO-led coalition estimated that it had killed 250 al Qaida fighters, captured hundreds more, and scattered as many as 800, including the top leadership.[30] The coalition had destroyed 11 training camps and 39 command posts, in addition to liberating the nation’s capital and second largest city, all with the use of fewer than 3,000 US military personnel.[31] By the spring of 2002 the USN and USMC had flown 12,000 sorties, representing 72% of all combat sorties flown during Enduring Freedom.[32] Between 7 October and 23 December, CENTCOM aviation flew 6,500 strike sorties, released 17,500 munitions, and destroyed 400 vehicles and artillery pieces.[33]

Refugees at the camp in Mazar-e Sherif, collecting aid from Doctors Without Borders, 23 December 2001, Staff Sergeant Cecilio Ricardo, USAF collection

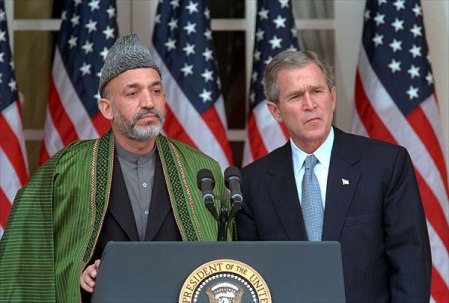

President Bush greets Chairman Karzai at the White House on 28 January, photos by Paul Morse and Tina Hager

Plans were now underway to introduce civilian stabilization measures, ranging from preparing a new Afghan school system to providing for vaccinations. Bush and Karzai, lauding the achievements of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) thus far, announced a joint New Partnership agreement during Karzai’s visit to the White House on 28 January 2002. Bush praised Karzai, stating that “the United States strongly supports Chairman Karzai’s interim government. And we strongly support the Bonn agreement that provides the Afghan people with a path towards a broadly-based government that protects the human rights of all its citizens.”[34] Karzai in return pledged to make Afghanistan an independent nation, fully backing the “joint struggle against terrorism… We must finish them. We must bring them out of their caves and their hideouts, and we promise we’ll do that.”

7 February, General Franks testifies to the Senate Armed Services Committee, chaired by Michigan Democrat Carl Levin. Republican Senator John Warner emphasized that the mission was almost complete, and Democratic Senator Landrieu emphasized the success of the Special Operations and Special Forces. General Franks emphasized the utilization of airpower, humanitarian airdrops, and that Afghanistan represented only one front in the broader war on terror, although in that theatre action had been taking place almost non-stop since mid-October.

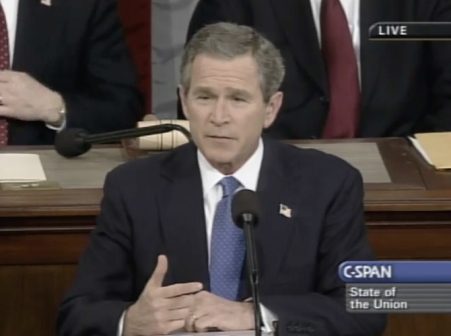

On new years eve the President appointed Dr. Zalmay Khalilzad, former Assistant Professor of Political Science at Columbia University and a ‘90s RAND cold warrior employed by National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, as his special enjoy for Afghanistan.[35] In his State of the Union address on 29 January, Bush unveiled the “axis of evil” – clearly indicating that Iraq was the next target in the Global War on Terror.[36] In fact, CENTCOM, in consultation with the Defense Department and the Vice President’s office, had been planning the invasion of Iraq throughout the entire duration of Operation Enduring Freedom.

Vice President Cheney and National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice talking in the White House Red Room, 13 February 2002, photograph by David Bohrer

Operation Anaconda

With hindsight it is clear that the greatest risk to mission success in Afghanistan came from within the Bush administration itself. From the outset the White House had established three essentially conflicting objectives. The first, liberate and sustain a rebuilt Afghanistan, was a mission with a clear objective that was backed by the international community and best reflected the capabilities of the United States. The second, the Global War on Terror, was an ideological mission imposed by Bush and the Republican neocons to justify unilateral anti-terrorist action world wide. Third, the planning for the invasion of Iraq, was an unrelated but long-held objective of the former George H. W. Bush and Ronald Regan cold warriors once again dominant in the White House.[37]

In a C-SPAN interview on 8 January 2002, Donald Rumsfeld was confronted by these conflicting objectives when a caller asked the Defense Secretary to define victory in the War on Terror, and to differentiate between Afghanistan the broader anti-terror mission. While the Secretary was clear that the mission in Afghanistan constituted deposing the Taliban and capturing or killing Taliban and al Qaida senior leaders – requiring in his opinion further effort to destroy the “pockets” of fighters who had not yet surrendered – he was less clear on what the objectives of the War on Terror were, or how it could be concluded.[38] Of course, it is now evident that there was no intention to conclude the War on Terror so long as it could be useful to justify US-led interventions against potential enemy nations, such as the “axis of evil” Bush outlined in his 2002 State of the Union address.

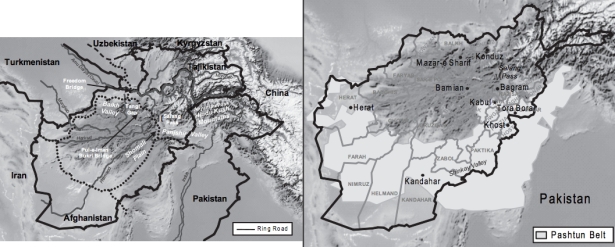

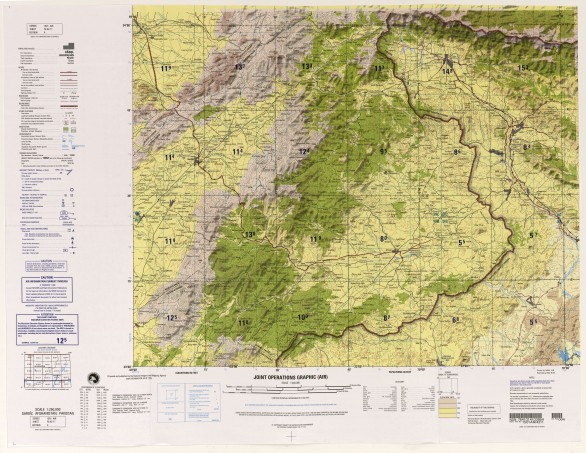

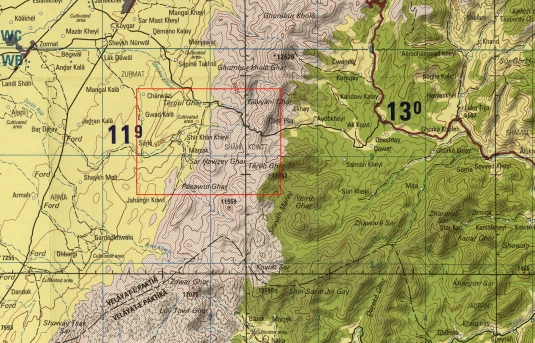

Joint Operations Graphic of the Gardez-Khost corridor

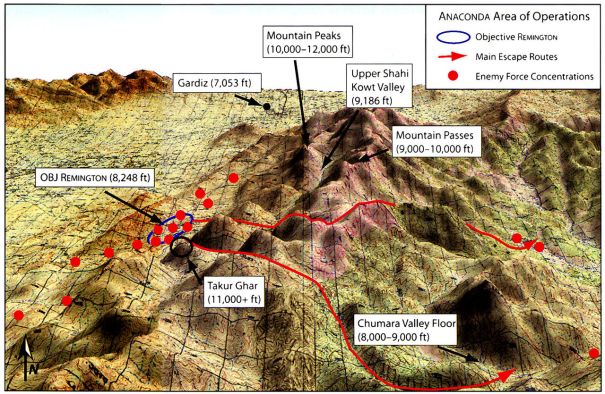

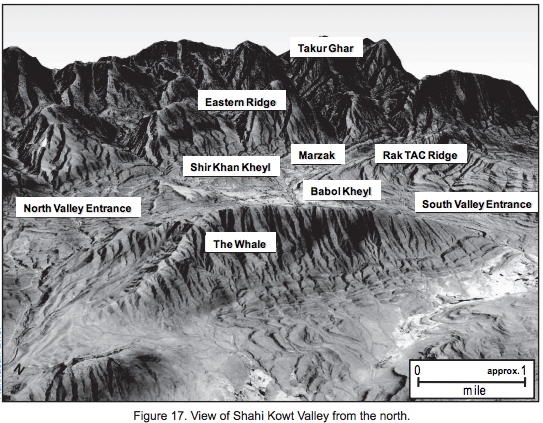

Shahi Khot Valley showing Operation Anaconda area of operations and Takur Ghar peak, & Shahi Khot valley with surrounding mountain ranges.

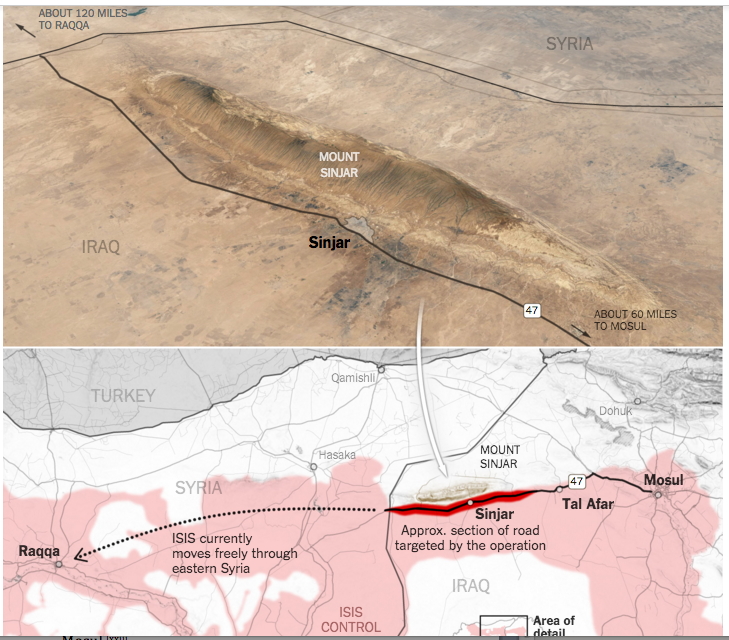

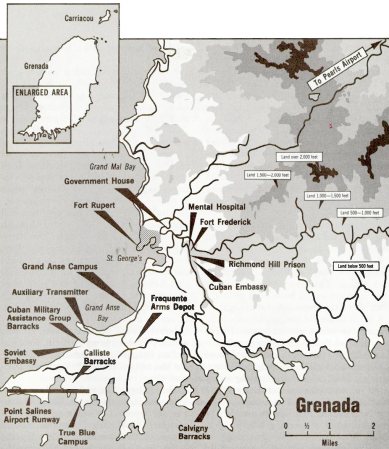

But what about the mission to liberate Afghanistan, and the pockets of Taliban and al Qaida fighters still in the country? At the beginning of 2002 the main al Qaida controlled route out of Afghanistan was through the Shahi Khot valley, bordering on Waziristan, south of Kabul. Late in January 2002 human intelligence provided by the CIA indicated that there was enemy activity south east of Kabul in the Paktia province, focused on the Gardez, Khost and Ghanzi area.[39] On 6 January JSOTF-N received orders to prepare “a sensitive site exploitation (SSE) mission in the Gardez-Khost region”,[40] and on 13 February Lt. General Mikolashek – his staff including the special operations coordinator Lt. Colonel Craig Bishop and Major General Hagenbeck – relocated the CFLCC to Bagram airbase in preparation for the upcoming operation, at which point the flexible and by now very much overtasked 167 staff officers of the 10th Mountain Division HQ became Combined Joint Task Force (CJTF) Mountain.[41]

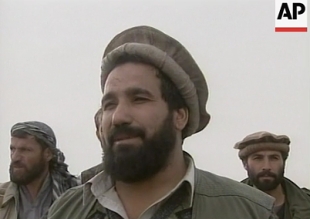

Commander Muhammad Smailzazi, CO Afghan Forces at Gardez, 10 March 2002, AP newsreel archive.

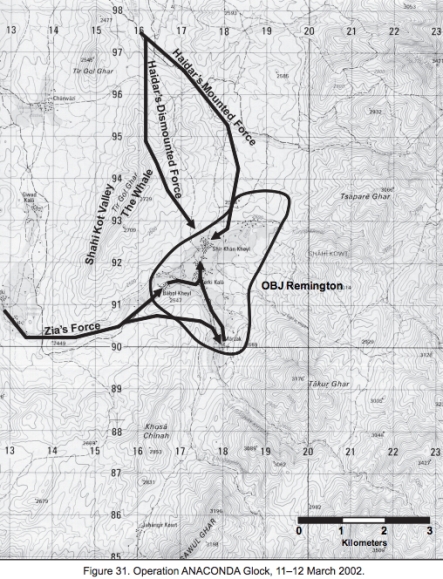

The following three weeks involved extensive reconnaissance, as the mission was organized and the Special Forces ODA teams integrated with their Afghan militia.[42] The CIA had designated a 10 km by 10 km box inside the 60 square mile Shahi Khot valley, 15 miles south of Gardez, that they believed contained the largest number of fighters. These combatants were holding key observation posts on the nearby mountains, and thus were in control of the villages between the mountain pass itself, although they were expected to attempt to retreat once the coalition arrived. By specifically isolating the escape routes the coalition intended to destroy or capture as many of the mujahideen as possible. The plan was worked out by CJTF Mountain and JSOTF-N staffs between 15 and 22 February.[43] Lt. General Mikolashek and Major General Hagenbeck both signed off on the plan, to which CENTCOM commander Tommy Franks also approved.[44]

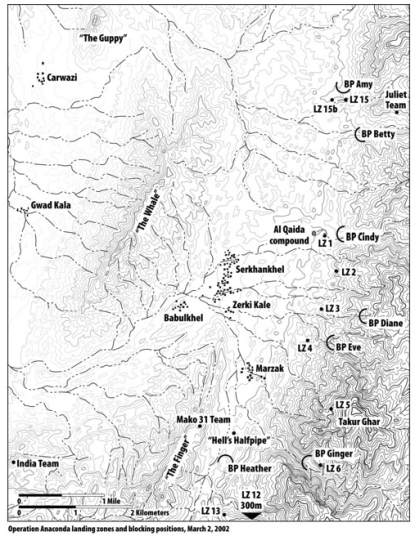

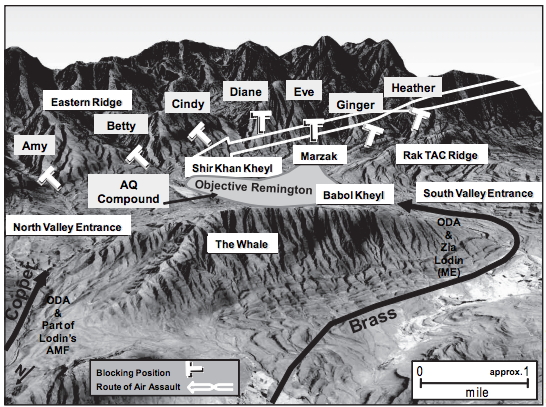

Designated Operation Anaconda, the plan called for the rapid deployment of blocking forces followed by a thorough, possibly weeks-long, sweep of al Qaida and Taliban forces in the Shahi Khot valley. This ultimately took place between between 2 – 19 March and involved more than 2,000 coalition forces, plus several thousand Afghans.[45] The objectives of the operation were fourfold: first, to locate the enemy forces known to be operating in the Shahi Khot; second, while Afghan and Green Berets elements pressured the retreating al Qaida fighters towards the east, to deploy a blocking force, composed of components of the 101st Airborne and 10th Mountain Division, to prevent the enemy’s escape into Pakistan; third, to capture the enemy held mountain overwatch positions by helicopter assault; and fourth, to capture or destroy any high valued targets (HVTs) hopefully in command of the fighters in the valley.[46] This would be the largest and most complex operation of the coalition’s war in Afghanistan since inception.

Enemy Forces

Jalaluddin Haqqani was the overall Taliban commander in the southeast, in the ‘90s having been governor of Paktia province, and was an experienced strategist and guerilla who fought the Soviets on numerous occasions, including in the Shahi Khot in December 1987 during Operation Magistral, when Soviet mechanized units and paratroopers forced the route between Gardez and Khost.[47] The local commander was Maulawi Jawad, who had under him Maulawi Saif-ur-Rahman Nasrullah Mansour, the senior fighter actually in the valley. The mujahideen had fled to Pakistan following the defeat of the Taliban in October 2001 but, by February 2002, Jawad had gathered as many as 1,000 fighters and then despatched a picked force to return to Afghanistan through the old mujahideen stronghold in the mountains above the Shahi Khot. American estimates of the number of fighters in the Shahi Khot ranged from the low figure of 150 – 250, to as many as 800 – 1,500 at the upper scale.[48] In fact there were 440 fighters in the valley: Rahman Mansour with 175 Taliban fighters, 190 mujahideen from Uzbekistan and Chechnya under Qari Muhammad Tahir Jan, and 75 Arabs – al Qaidi fighters – from various countries including Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Morocco, Somalia, Jordan and elsewhere.[49]

Approximate battle area, centred on Tergul Ghar, “the whale”, the village of Shir Khan Kheyl, and the passes through the mountains to eastward.

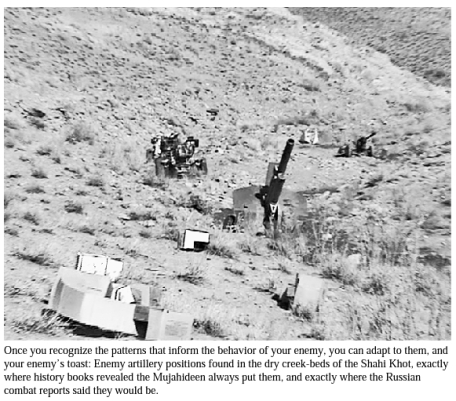

The mission profile suggested that the CJTF believed the lower figure of only 150 to 200 was accurate, and so it came as quite a surprise when TF Rakkasan landed amidst a valley held by significantly more than double that number of fighters.[50] The Shahi Khot valley, the low “Whale” of Tergul Ghar to the west, and the foreboding Eastern Mountains which flanked the passes to Pakistan, had been well fortified by the mujahideen since the Soviet era.[51] The pashtuns had fought the Russians here in 1981, cutting the supply line between Gardez and Khost.[52] The mujahideen made the Shahi Khot a source of constant irritation for the USSR, ambushing Soviet forces trying to secure the Gardez – Khost roadway on numerous occasions: March 1982, August 1983, November 1984, August 1985, and November 1987. Thus the Shahi Khot, despite numerous Soviet attempts to clear the valley, remained a mujahideen stronghold after the Soviets withdrew in 1988.[53]

CJTF Mountain

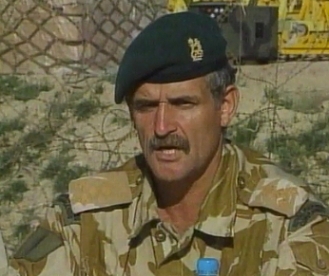

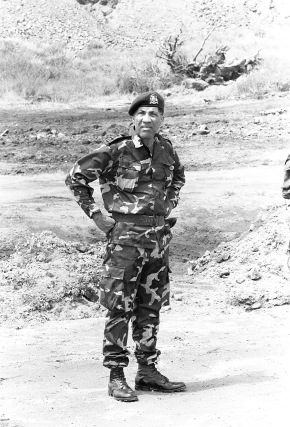

Brigadier General Hagenbeck in June 2000, & Lieutenant General Franklin Hagenbeck, photographed in October 2006. CO CJTF Mountain

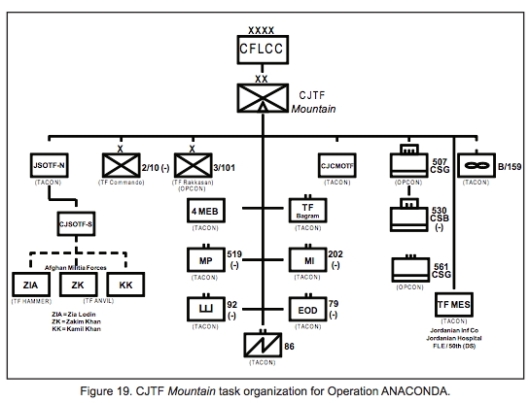

CJTF Mountain, from Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War

The Coalition force selected to carry out Operation Anaconda was representative of the diverse mix of joint elements: a multinational force including soldiers from several Northern Alliance commanders, American Green Berets, CIA operatives, JSOC represented by SEAL Team Six, Delta Force squadrons, Army Rangers, and the USAF’s Combat Controllers, rounded out with Australian SAS, Canadian regulars and TF Rakkasan, the mixed 10th Mountain and 101st Airborne conventional forces.

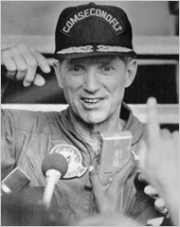

TF Rakkasan CO, Colonel Frank Wiercinski, 187th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Brigade, 101st Airborne Division, 12 February 2002.

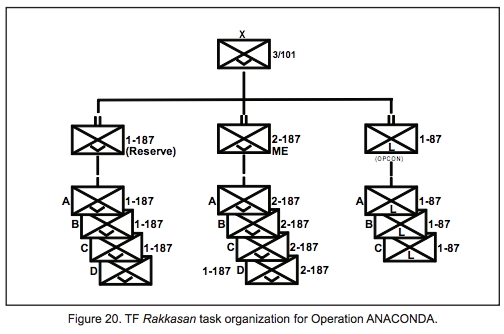

TF Rakkasan organization, 101st Airborne Division, from Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War

The coalition CJTF Mountain was itself commanded by 10th Mountain Division CO, Major General Hagenbeck. Operation Anaconda drew on elements from every component of CJTF Mountain, creating a confusing web of C2 that was in fact unprecedented in SOCOM history. At least nine nations were involved.

The various SOCOM and conventional Task Force designations were as follows:

TF Sword (aka, TF 11: JSOC), Major General Dell Dailey and USAF Brigadier General Greg Trebon (deputy CO JSOC), their AFO coordinator was Lt. Colonel Pete Blaber, Delta Force.[54]

TF Red (Rangers, CO Tony Thomas).

TF Green (Team Delta)

TF Blue (SEAL Team 6, DEVGRU, Joseph Kernan).

The Army’s Chinook helicopters were from TF Talon (Lt. Colonel James Marye).[55]

The 160th SOAR also provided their 1st and 2nd battalions, Chinooks, for the SOCOM missions, as TF Brown. TF 58 was the USMC designation.

Both Kernan and Thomas had elements in reserve at Bagram and Kandahar in the event an HVT was located and extraction was required on short notice (they also constituted the QRF force), although the flight out to the Shahi Khot at this distance would take at least an hour.[56]

Unidentified coalition soldiers boarding a C-17, 14 March 2002, AP newsreel archive

Afghan National Army training at Gardez.

The Special Forces units employed were drawn from the two major commands that had so far run the SOCOM war in Afghanistan:

Joint Special Operations Task Force-North (JSOTF-N), out of the K2 base in Uzbekistan, CO, Colonel John Mulholland, 5th Special Forces Group, with 1st Battalion under Lt. Colonel Chris Haas, plus Delta A Squadron and a smattering of CIA operatives. CO Mulholland committed five SF teams to Anaconda: ODA 542, 563, 571, 574, and 594, plus TF 64, the Australian SAS.[57] This command was also known as Task Force Dagger (Northern).

Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force-South (CJSOTF-S, CO Captain Robert Harward) at Kandahar,[58] with a collection of SOF forces including teams from Denmark, France, Germany and Norway, loaned to Anaconda 3rd SFG ODAs 372, 381, 392, 394 and 395.[59] This command was also known as Task Force K-Bar (Southern).

Blaber, Haas, with ODA 510, and the CIA (led by a man named Greg – “Spider”) were installed at Gardez, population 70,000, the capital of Paktia province, where the 50-strong SOCOM operators were variously involved planning, gathering intelligence, and training Zia Loden’s 400 strong Afghan militia contingent.[60]

The Plan

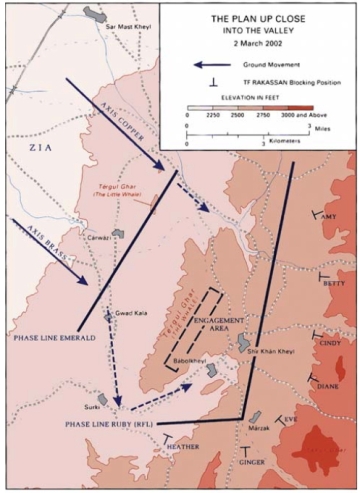

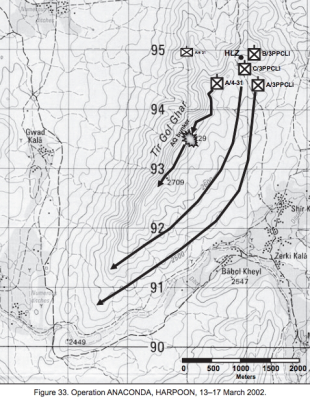

Coalition approach vectors, showing approach axis (Brass and Copper), and phase lines (Emerald and Ruby), from Leigh Neville, Takur Ghar (2013), p. 17

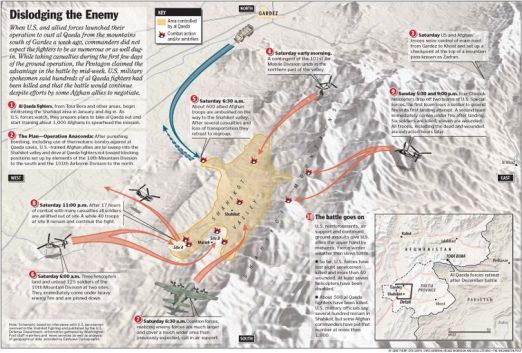

TF K-Bar would conduct the pre-operation reconnaissance, ultimately inserting 21 various teams for this purpose.[61] The TF 11 AFO teams would infiltrate several days in advance and secure the mountaintop observation points, before TF Rakkasan deployed the morning of, what at that time was still scheduled for, 1 March into the eastern Shahi Khot to secure the valley exits.[62]

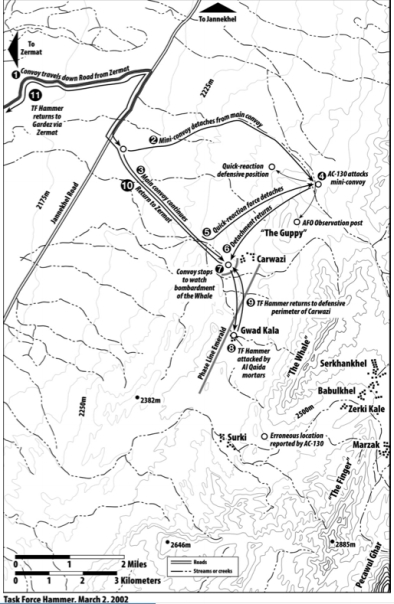

Task Force Hammer would make the main drive from Gardez to the Shahi Khot, retrieve the AFO elements, and then clear the valley starting with the village of Babulkhel.[63] ODA 372, led by the 34 year old Chief Warrant Officer 2 Stanley Harriman, would lead the mixed SOCOM force, convoying trucks carrying Zia’s Afghan fighters, ranging from 400 to 600 strong, with Zakim Khan (ODA 542, 381) and Kamel Khan (ODA 571, 392) both fielding reserve forces of 400 – 500 each for what was designated Task Force Anvil, that force meant to drive towards the Shahi Khot from the east, ie, from Khost, hopefully encircling the enemy in the valley and enabling TF Hammer to sweep into the valley from the west.[64]

The helicopter assault force, Task Force Rakkasan, with the vital objective of securing the “inner ring” of seven blocking positions (BPs),[65] was commanded by Colonel Frank Wiercinski and composed of battalions from the 101st Airborne and 10th Mountain Division. Lt. Colonel Charles Preysler’s 2/187 (2nd Battalion, 187th Infantry Regiment), and Lt. Colonel Ronald Corkran’s 1/187 (1st Battalion, in reserve at the Shahbaz Air Base, Jacobabad), plus the 10th Mountain Division’s 1/87th (1st Battalion, 87th Infantry Regiment) commanded by Lt. Colonel Paul LaCamera, and lastly attached at Kandahar was the 3rd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry.[66] For the purposes of Anaconda, the Canadians were attached to CJTF Mountain, while 1/187 was attached to the CFLCC HQ, Lt. General Paul Mikolashek.

TF Rakkasan’s mission was to helicopter into the Shahi Khot and for 2/187 to secure the northern four BPs and 1/87 the southern three BPs. The helicopter assault would be escorted by the 101st Division’s Apaches, the gunships had the responsibility of determining if the LZs were clear or not.[67] Preysler intended to have Captain Frank Baltazar’s C Company secure BPs Betty, Cindy and Diane, leaving BP Amy for the second wave, Captain Kevin Butler’s A Company, at H+11.[68] BP Eve would be taken by Captain Roger Crombie’s 1/87 A Company, while Captain Nelson Kraft’s C Company would take Ginger and Heather.[69] Once these forces were deployed, Wiercinski would insert to small tactical control (TAC) post near BP Heather (on the slopes of the mountain nick-named “the Finger”), with some of Lt. Colonel Corkran’s 1st Battalion HQ, to monitor the situation in the valley in the event the reserves needed to be deployed.[70]

Generals Hagenbeck and Mulholland briefed General Franks by video conference on 26 February, and D-Day was set for 28 February, although this was delayed 48 hours to 2 March due to white-out weather conditions.[71] TF Anvil drove west from Khost on 1 March and established its blocking positions behind the eastern mountains.[72]

Reconnaissance, 27 February – 1 March

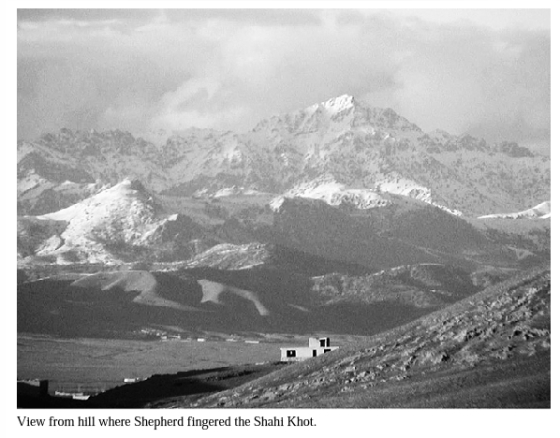

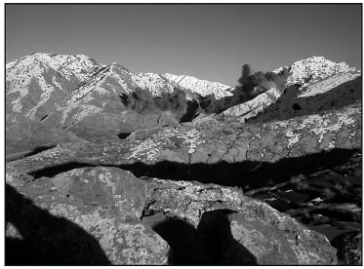

The Shahi Khot valley, from Pete Blaber, The Mission, The Men, and Me (2008). Note the imposing snow capped Eastern Mountains, also note the aridity of the terrain: extremely difficult for the recon teams to exploit given the lack of concealment.

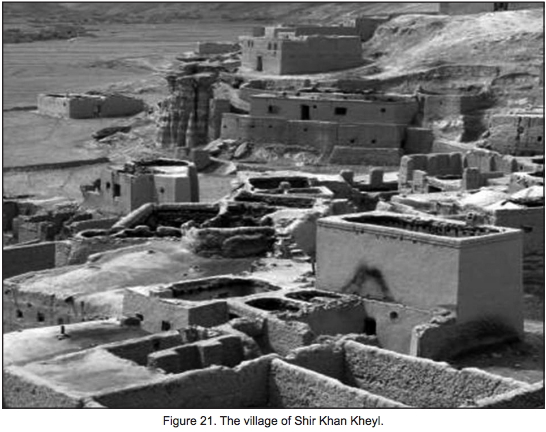

A critical component of the plan was to insert three of Lt. Colonel Blaber’s AFO elements to identify and knockout enemy positions covering the valley entrances, prior to the arrival of the main force. Generally successful, the recon teams made difficult hikes into enemy occupied territory and identified key over-watch positions from which to call in air strikes. Intelligence was spotty, but there were believed to be as many as 1,400 civilians and non-combatants in the three villages in the valley, Shir Khan Kheyl (or Serkhankhel), Babol Kheyl (or Babulkhel), and Marzak.[73]

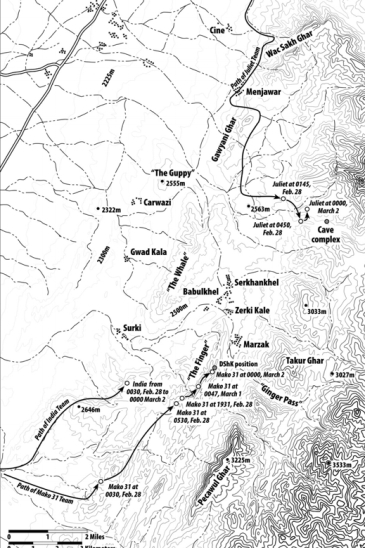

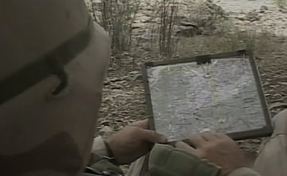

The AFO teams were divided into two Delta Force elements, Juliet and India, and a SEAL element, Mako 31. Once in position these teams would hold their sniper and air controller posts and provide overwatch before TF Hammer and TF Rakkasan arrived at H-Hour (6:30 am) on 2 March.[74] The 1:100,000 maps the operators had been issued for their initial prior environmental reconnaissance had proven insufficiently detailed for the kind of, craggy, snow-covered terrain they were crossing.

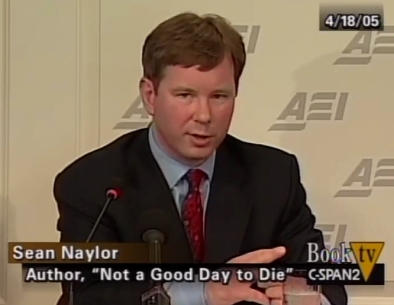

India, Juliet, and Mako 31 routes, from Sean Naylor, Not a Good Day to Die (2005), p. 162

Juliet, India, Mako 31

Juliet Team, the northern five-man reconnaissance element led by Delta operators Master Sergeant Kris K. and Bill R., and supported by an Intelligence Support Activity (ISA), Gray Fox operator named Jason, drove in on ATVs, covering twelve kilometers through enemy held territory including the village of Menjawar (Menewar), that they navigated through at midnight.[75] Using JSTARS aircraft surveillance in combination with laptop GPS, the operators made their way north of the valley, designating a minefield and a pair of occupied DShK machine gun positions for the B-1s to strike, enroute to their south facing OP where they arrived between 4:45 – 4:47 am.[76] The Juliet team, from its position looking across the valley, could see the Takur Ghar peak and opposite it enemy positions, including mortar pits, along “the Whale” – the spine of the Tergul Ghar mountain.[77]

As the Juliet team was motoring north into the valley, John B’s SOF (three Delta and one SEAL Team Six operator) and Afghan fighter units were driving a pair of Toyota 4×4 pickup trucks, ferrying India Team, a three-man Delta recon element, and Mako 31, a five-man SEAL team, to their insertion points.[78] The recce elements departed at about 10:15 pm to hike into their positions at the southern end of the Tergul Ghar “Whale” and the north-facing prominence “the Finger” at the western approach to the valley, where they would have clear line of sight both of TF Hammer’s approach and the valley proper.[79] After deploying the recce teams, John B. and the Afghan fighters turned around their two Toyotas and started the drive back to Gardez.[80]

India team, led by “Speedy” and Bob H. (both Delta Force, armed with M4 carbines) and Dan (ISA, carrying an SR25), started their seven kilometer hike alongside Mako 31, following the Zawar Khwar creek, until three kilometers in at which point they turned north towards their OP.[81] The weather was at first poor, with intense sleet and snow, but by 5:22 am they were in position and undiscovered.[82] Speedy made satellite radio contact with Gardez at 9 am on the 28th.[83]

Mako 31, the five-man element, was composed of SEAL operators – three Team Six snipers and a demolitions expert armed with an M4 – plus their AFO, Andy. They started their hike alongside Delta’s India element but then diverted for the 11 km hike to their OP on “the Finger”. The round-about route combined with poor weather delayed the hikers, who had to take a position about a kilometer from their OP before daybreak. Between 5 and 5:15 am on the 28th they reported in to Gardez, informing Blaber, the AFO commander, that they would hunker down until the following night to make for their OP.[84]

The Juliet team, employing their thermal and night optics, spotted numerous mujahideen moving around on Tergul Ghar. Kris called Blaber on their satellite radio and informed him that “the Whale” was infested with enemy positions.[85]

The morning of 28 February India split up and moved into deeper cover as daylight revealed how exposed their OP actually was.[86] Speedy spotted a goat-herd and his flock below their position, but luckily avoided compromising the OP. Mako 31 meanwhile moved into a better position to view the roads heading east into the valley.

The three recce elements deployed telescopic lenses and Nikon handheld cameras to develop their intelligence while the AFOs and ISA operators designated targets for future air strikes. India could see that the TF Hammer approach was clear of mines and the village of Surki at the valley entrance appeared to be deserted.[87]

The two ISA operatives with the Delta teams detected radio and cellphone traffic, and around noon Mako 31 heard sporadic gunfire – presumably training – coming from the direction of Marzak.[88] Juliet by now also had positive IDs on a group of five men armed with AK47s and RPGs who, worryingly, seemed to have detected their ATV tracks and were moving in their direction, although they turned around at the last moment due to an approaching blizzard, and departed the area without discovering the AFO team.[89]

Sometime before the blizzard arrived the CIA employed an Mi-17 helicopter to film the valley, in search of enemy locations.[90] The weather then worsened as the blizzard carpeted the valley. Juliet took advantage of the two-hour long snow storm to booby-trap their ATVs and move camp to a higher position. The operators spotted another four suspected fighters on Tergul Ghar during breaks in the weather.[91] A few hours later they had identified at least several occupied positions: one fighter facing west on the Tergul Ghar ridge, another two in a camouflaged rock shelter nearby, and four more fighters moving between two shelters on the eastern side of the ridge, plus additional positions fifty meters below the ridge.[92] Mako 31 later confirmed these enemy positions.[93] Clearly “the Whale” was both occupied and well defended – knowledge that had thus far gone unnoticed to all of the aerial observations, suggesting the mujahideen’s mastery of camouflage as a cultivated experience from the Soviet war.[94]

India, meanwhile, could also hear the gunfire Mako 31 had reported in the direction of Marzak, although their OP was soon obscured by the weather and they were forced to rely on the ISA communication intercepts, the latter which were eventually relayed to Bagram for aircraft reconnaissance, as well as to the NSA for satellite tasking.[95]

At this time H-Hour was still set for 6:30 on 1 March, but Hagenbeck now made the decision to delay another 24 hours due to the weather.[96] Mako 31, by 2 am on 1 March, had moved to within 250 meters of the peak of “the Finger” the heights south of the valley.[97] Just after dawn Goody despatched his Team Six snipers to the ridgeline, and, after crawling for 500 meters, they spotted a large tent with attached stove pipe, and nearby a tripod mounted DShK machine gun. Mako 31 soon spotted two al Qaida fighters, who Goody at first suspected might be British SAS, a conclusion that was denied when Goody emailed digital photos back to Blaber at Gardez using the team’s laptop and satellite phone interface.[98] The SEAL Team Six officer knew the importance of knocking out the machine gun position, Blaber having briefed him that “the success or failure of your mission will predicate the success or failure of the entire operation”.[99] Blaber informed Hagenbeck of the enemy positions, and authorized Goody to wait until about an hour before H-Hour the next morning, and then knock out the machine gun before calling in an AC-130 gunship strike on the position.[100]

The village of Shir Khan Kheyl from Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War

While the debate behind the lines was ongoing regarding the mission plan, in the Shahi Khot all the evidence was building towards a significant enemy presence in well concealed and defended positions. India reported three SUVs driving inside Babulkhel, near the valley entrance, and then three horsemen approaching the village. The horsemen were greeted by six men with Kalashnikovs. Speedy and Bob identified two occupied walled compounds in Serkhankhel, and spotted several women and a family, the only unambiguous sighting of civilians by any of the recon teams. Juliet’s view was at first obscured by clouds but as the weather cleared in the afternoon, and they were joined by a high-flying Predator drone, they also spotted armed men in pickup trucks moving around inside Serkhankhel.[101] Jason, the ISA operator, intercepted a call that he believed indicated a “group meeting” was being held that day.[102] Juliet spotted a group of six men carrying rucksacks moving back into Serkhankhel from a position no more than a kilometer from where the Delta team was observing (possibly the patrol that had almost discovered their ATVs before the blizzard).[103] By now both India and Juliet teams had seen enough enemy presence to convince them that the helicopter assault would be heading into a cauldron: the valley was not a series of villages with a hidden al Qaida presence, but in fact a mujahideen stronghold.[104] Familiarization with the conduct of the Soviet war confirmed the truth of this.[105]

Thinking about the implications of this intelligence Jimmy, Blaber’s deputy, went directly to Colonel Joe Smith, Hagenbeck’s chief of staff, and recommended changing the operation plan to better reflect the scale of the enemy presence. “The current plan is not going to work out for you,” Jimmy advised Smith. “I know, Jim,” said Smith, “but it’s too late to do anything about it.” Smith, according to Naylor and Blaber, turned down Jimmy’s request.[106] Hagenbeck, however, did inform Lt. General Mikolashek via video teleconference that there were many new positions they should airstrike before sending in TF Hammer. “Bomb these frickin’ things,” Hagenbeck said, according to Mikolashek. Air Force General Renaurt, Franks’ Director of Operations, again stated that the plan could not be changed at the last minute.[107] As a frustrated Pete Blaber wrote later, summarizing a fundamental truism regarding failed planning processes from time immemorial, “…the mission itself no longer had anything to do with the reality on the ground; the mission was to execute the plan on time.”[108] Ironically, the senior Taliban commander in the valley, Saif Rahman Mansour, was at that time making essentially the same error.[109]

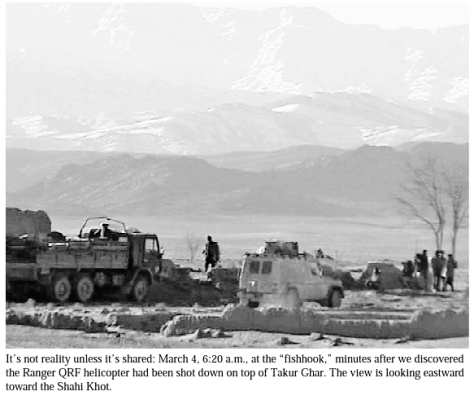

At any rate the AFO teams managed to remain concealed for the remainder of 1 March and when night fell they received air support in the form of Grim 31, an AC-130H gunship, that arrived over the engagement zone at 2:04 am. At 2:55 am the India recce element spotted the headlights of TF Hammer as the main column drove south from Gardez along the muddy Zermat road to its planned staging ground at the Shahi Khot entrance. TF Hammer, with Ziabdullah and Chief Warrant Officer Harriman, ODA 372, in the lead vehicle (a HMMWV), would divide into two convoys: Harriman’s group heading to block the valley entrance north at a terrain feature known as “the Guppy” while the main body continued to the southern entrance known as “the Fishhook”.[110]

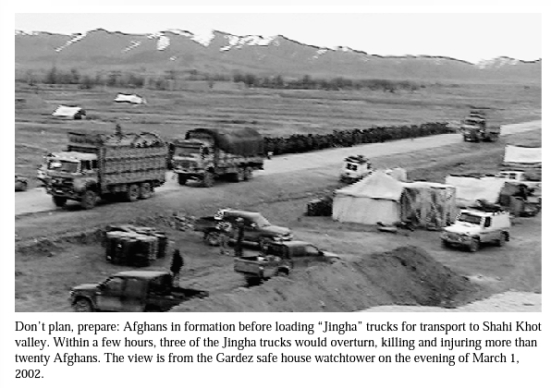

Some of TF Hammer’s trucks and vehicles viewed from their assembly point in Gardez, from Pete Blaber, The Mission, The Men, and Me (2008)

TF Hammer’s main column was commanded by McHale, Glenn Thomas, and Lt. Colonel Haas, and was composed of 39 or 40 vehicles, mainly pickup and flatbed trucks, consisting of a mix of SF (ODAs 594 and 372), SEALs, AFOs, CIA, Australian SAS, and an engineering squad attached to TF Rakkassan: this mixed coalition force supported 400 Afghan soldiers under Zia Loden and Ziabdullah, together having assembled at Gardez and then, at 11:33 pm on 1 March, commenced the treacherous two hour-long drive south.[111] Two trucks had to be sent back carrying wounded after a pair of vehicles became stuck in the mud and a third overturned.[112] They were already behind schedule, the plan being for TF Hammer to arrive at Phase Line Emerald, 1.5 km west of Tergul Ghar, while the pre-assault air strikes took place (about 5:30 am).

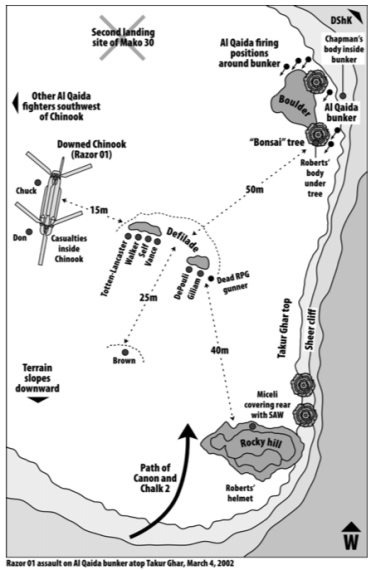

Around midnight meanwhile, Mako 31 was getting ready to move. Goody and Chris, armed with their suppressed SR25s, started to surround the DShK machine gun position while Andy, their AFO, called in P3 Orion and Grim 31 AC-130 coverage. At about 4 am Goody and Chris were spotted by a sentry.[113] With no choice but to attack, Chris and Goody charged towards the enemy tent, but their rifles jammed due to icing.[114] The sentries returned fire with their AK47s. A Chechen fighter charged Chris but was shot after the operator cleared his jam. Several fighters were killed fleeing the tent,[115] while another fighter tried to man the DShK but was shot before he could reach it. Meanwhile Eric was watching for fighters who might be attempting to flank them. Andy informed Chris that Grim 31 was ready to destroy the DShK position once the operators had withdrawn from their danger close positions. Andy received information from the sensor-laden AC-130 that there were at least two more fighters about 75 meters to their north. These fighters were in fact deploying a PKM machine gun, with which they quickly opened fire on Mako 31.[116] As the operators fell back, it was now approximately a quarter after four, the AC-130 gunship hovering above fired its 105 mm cannon, plastering the enemy camp and killing the machine gunners and several other nearby fighters.[117] This action, resulting in the death of the five al Qaida guards in the outpost, was the first combat of the operation, to be followed shortly at 4:44 when Grim 31 carried out a strike ordered by the Juliet AFO against an enemy OP on “the Whale”. These mountain top gunfires generally alerted the mujahideen around the valley that they were under attack from coalition forces.

When they checked the bodies of the enemy fighters they had killed on “the Finger” Mako 31 found evidence indicating that they were Arabic speaking Uzbeks and Chechens. The well serviced DShK position was armed with 2,000 rounds and included an SVD sniper rifle, several AK47s, the PKM automatic rifle, plus seven RPGs for a single launcher.[118] Mako 31 requested Grim 31 do another flyby of “the Finger” to verify there were no more enemy fighters, then phoned in to Blaber that they had terminated the threat, and hunkered down as dawn was breaking to watch TF Rakkasan arrive within the hour.[119]

Air Assault, 2 March

H-Hour was set for 6:30 am on 2 March, and was to be preceded by a 55 minute window for air bombardment. 2/187’s infantry would then make the first landing, followed by 1/87, the 10th Mountain troops, while 1/187 was held in reserve. The TF Rakkasan soldiers and officers had been preparing since 16 February, conducting their final rehearsal at Bagram on 28 February.[120] Senior NCOs were making it clear to the picked troopers that this was a combat mission.[121] The assault packaged continued to undergo last minute changes, with the second wave of troops being brought forward to three hours following H-Hour (ie, scheduled to arrive at 9:30 am), instead of the evening as had originally been planned, to provide ample forces for the blocking operation.[122]

TF Rakkasan paratroopers boarding CH-47D helicopters during an exercise in the Shahikot, from Leigh Neville, Takur Ghar (2013), p. 18

At half past noon on 1 March the TF Rakkasan commander, Colonel Frank Wiercinski, was in Bagram’s chow tent briefing the 60 helicopter pilots and chief warrant officers (CWO) of TF Talon.[123] The Apaches were drawn from 3rd Battalion, 101st Aviation Regiment, the “Killer Spades” and were split into three groups of two, tasked with ensuring the LZs on the valley floor were clear. Wiercinski reiterated the importance of the Apaches for providing escort to the Chinook groups: “It will be on my word that we unleash hell,” he said, quoting Gladiator. From the roof of a Humvee Wiercinski gave a speech to the entire assembled battle group of 1,700, quoting from Saint Crispin’s in Henry V.[124]

Early the following morning the Apache pilots boarded their six gunships and were warming them up at 4:37 am for their 5:07 launch time. They would escort the Chinooks in and then take up attack positions in the last minutes before the air strikes started, and then remain on station until 7:35 when they were scheduled to fly the 80 km back to midway fueling station “Texaco” already established between Bagram and Objective Remington.[125] Due to a last minute hydraulic leak in the 30 mm cannon aboard Team 2 Chief Warrant Officer Bob Carr’s Apache, Captain Bill Ryan, commanding the Apache flight, merged Team 3 into Team 2 so that Carr could stop off at the “Texaco” fueling point and make repairs.[126]

TF Hammer’s approach to the Shahi Khot, note Phase Line Emerald west of “the Whale” and also the location of the friendly-fire incident on Harriman’s convoy, from Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War & from Sean Naylor, Not a Good Day to Die (2005), p. 187

After Mako 31 was forced to reveal themselves early, and the hydraulic leak in Carr’s Apache, the third major upset of the initial phase of the operation took place: At 5:30 am the AC-130 gunship Grim 31 mistakenly engaged Harriman’s four vehicle lead element. The eight rounds of 105 mm cannon they fired wounded several of the Special Forces, including Harriman himself who was hit in the back by a piece of shrapnel that punctured the door of the Hummer he was a passenger in, also wounding seven others and killing two of Ziabdullah’s fighters.[127] All four of Harriman’s vehicles were destroyed.[128] As soon as this unfortunate fire mission was delivered Grim 31 announced that they were low on fuel and departed, to be replaced on station by a flight of F-15Es.[129] Blaber and Glenn P. in Gardez quickly ordered a ceasefire when it became apparent from the AFO reports from the main TF Hammer column that Grim 31 was engaging Harriman’s northern element.[130] The main column despatched its four vehicle QRF, led by CWO2 Sean Ballard in an armoured SUV and including ODA 372 medic Sergeant First Class Brian Allen, who reached Harriman’s convoy ten minutes later.[131]

B-52s flying above the Shahi Khot on 5 March 2002, AP newsreel archive

At 6:30 the pre-planned air strikes started, including a B-1B, a B-52 and the two F-15s already on station.[132] A thermobaric bomb destroyed one of the cave complexes on Juliet’s target list, and the B-1B dropped 6 or 7 JDAMs on “the Whale” – but delays caused when the B-1B’s rotary launcher jammed added to concerns over hitting the AFOs in the valley, with the result that only a few of the designated targets were hit before the air assault commenced.[133] By now the friction of war had dramatically derailed the assault plan.

CH-47 Chinooks in formation, with Apache overhead, MH-53 at right, 11 March 2002, & Chinook and Blackhawk helicopters leaving Bagram, 14 March 2002, AP newsreel archive

The initial components of 2/187 battalion in their Chinooks was already on the way south from Bagram. The lead Chinook element was informed by the airborne AWACS “Bossman” that they would need to stop on their way back to retrieve the wounded from Harriman’s convoy.[134] The TF Talon helicopters circled around the valley to the south and then entered from the east. The first and second wave of three Chinooks arrived at their LZ and dropped off their infantry while the Apaches circled over head.[135] Hearing the reports of heavy combat in the Shahi Khot, Hagenbeck made the decision to hold off sending in the second wave of Chinooks until the situation had cooled down. The mujahideen meanwhile rushed in their reinforcements to surround the landing zones.[136]

On the way back to Bagram the Chinooks landed at Harriman’s location and picked up the wounded. At Bagram Harriman was tended to by medics from the 274th Forward Surgical Team, but his wounds were mortal.[137] The TF Hammer QRF departed the accident area, leaving two AFO personnel, John B. and Isaac H., behind to establish an OP, as the sun was rising.[138]

McHale, leading the main TF Hammer column, continued south towards the village of Gwad Kala to the west of “the Whale”, that was expected to be deserted. When he arrived he was met by Thomas and appraised of the situation at the rear of the column, which necessitated unloading several of the forward trucks so they could be sent back to replace breakdowns.[139] McHale was in the process of deploying his Afghan platoon into a nearby wadi when he began to receive mortar fire directed at Gwad Kala from “the Whale”.[140] McHale, with rounds exploding nearby, thought the best option was to get back aboard their trucks and move out. Several of his SF NCOs could see the puffs of smoke on the slope in front of them from enemy mortars firing.[141] Sergeant First Class John Southworth, the designated radio operator for TF Hammer, was able to get in touch with the Apaches to request assistance, but Zia Loden, who was expecting greater air support and had now sustained casualties from the blue-on-blue incident against Harriman’s convoy, refused to attack further. This effectively terminated the TF Hammer mission, although had it actually driven through “the Fishhook” and into the valley it certainly would have taken more casualties from the surrounding ambush positions.[142]

Landing Zone (LZs) and Blocking Positions (BPs) from Sean Naylor, Not a Good Day to Die, p. 228. BPs are only approximate. Note the locations of the AFO teams, Mako 31 & Juliet. India was on the southern tip of “the Whale”.

View of Shahi Khot Valley and concept of operations, from Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War. Note the seven blocking locations.

Apache pilots Hurley and Chenault, meanwhile, were busy attempting to identify and destroy enemy positions on the six kilometer-long ridgeline surmounting “the Whale”.[143] The two Apaches of Team 1 destroyed an eight-man mortar pit and surrounding area with rocket fire, and Chenault spotted tracer fire from a machine gun attempting to engage Hurley.[144] The Team 1 Apache moved back to the northeastern side of “the Whale” searching for a second reported mortar position, while the Team 2 Apache was taking fire from the southern valley. A lucky hit from a machine gun bullet in fact disabled several of the electrical systems associated with navigation and weapons control aboard Hardy and Pebsworth’s Apache, rendering their weapons useless.[145]

Apache gunship on 2 March, from Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War

Shortly after this Hurley, flying the second Team 1 Apache, used his cannon and rockets to engage a four-man RPG team that he had spotted aiming at Chenault’s Apache.[146] After looping around for another pass Hurley and Contant’s helicopter was hit by an RPG, destroying the Apache’s left Hellfire pylon, which had carried three missiles, and in the process wrecking the left rocket pod. Gunfire pelted the helicopter, by now leaking oil and smoking, and at least one round penetrated through the cockpit and became lodged in the console in front of Hurley.[147] Hardy and Pebsworth’s Apache was likewise still taking RPG and machinegun fire, and with their weapons system already disabled they moved into formation with Hurley and Contant’s Apache and together the two damaged helicopters retired to the Texaco waypoint to rearm and repair, although within minutes the loss of transmission fluid forced Hurely to land in a nearby creek bed, Hardy also landing nearby. From there Hardy, the more experienced pilot and technician, swapped pilot’s chairs with Hurley, poured their reserve oil into the badly damaged Apache, and lacking fully functioning navigation instruments, took off again to arrive 26 minutes later at the Texaco fueling point, which was quickly developing into the logistical waypoint for the entire operation.[148]

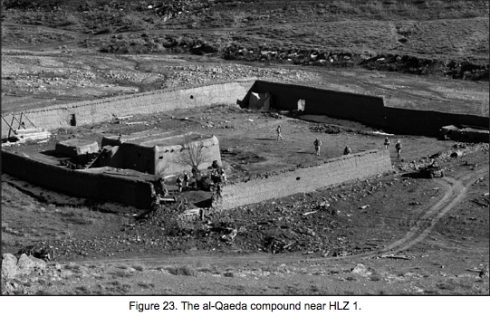

At 6:15 am Captain Frank Baltazar’s 2/187 C Company, 2nd Platoon, and elements of Lt. Colonel Preysler’s HQ, deployed from their Chinooks in the center of the valley and began securing a perimeter. C Company’s three platoons were spread out around the valley at different LZs, with 3rd Platoon landing at LZ 4 for their march to BP Diane, 1st Platoon landing at LZ 3 for BP Cindy, and 2nd Platoon with all the HQ elements landing at LZ 1. Their immediate objective was to clear a small al Qaida compound that had been identified in recent reconnaissance photographs. All three platoons were taking fire: the 2nd Platoon LZ was fired upon from a machine gun position 400 meters away, actually on a ridge behind the compound.[149] Two of the company’s machine gunners returned fire, supressing a pair of fighters before the position was destroyed by an Apache strike that Preysler had ordered.[150]

As 2nd Platoon was clearing the compound they discovered that it had been recently occupied. The mujahideen, who had fled to the surrounding hillside, had been heavily equipped, their stash containing “several recoilless rifles, [2] 82 mm mortar tubes and rounds, dozens of AK-style assault rifles and RPGs, Dragunov [SVD] sniper rifles, three [or 1?] sets of U.S. PVS-7 night-vision goggles, binoculars, and handheld ICOM radios that Sergeant First Class Anthony Koch, the troops’ platoon sergeant, said ‘were better than ours.’” Other debris included a Nike sports bag originally from Beaverton, Oregon, 50 alarm clocks and an assortment of wrist watches, in addition to a quantity of foreign currency.[151] The compound had six beds, and the fighters who had scrambled out had left behind not only their still brewing tea but also their shoes.[152] The compound was soon taking gunfire from the surrounding hills, and Preysler attempted to call in 120 mm support, but his forward observer discovered that the mortar, at the southern end of the valley with Kraft’s company, had already been engaged.[153]

Preysler decided to set up his HQ just outside the compound and called in Apache helicopter and Predator drone attacks, which quickly combined to silence the enemy who were firing on them from the vicinity of BP Cindy.[154] At about 7 am Preysler now informed Baltazar that he wanted them to move, with 2nd Platoon, to secure BP Betty to the northeast.[155] This took five hours to accomplish, by which time 1st Platoon had taken BP Cindy and 3rd Platoon BP Diane.

The compound 2nd Platoon, C Company, 2/187, was ordered to take near LZ 1, at the northeastern side of the valley, from Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War

The situation in the north, 2 March, from Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War

Sergeant First Class Kelly Luman of 3rd Platoon had responsibility for securing BP Diane, the easternmost position on Hill 3033, with Preysler’s Scout Platoon about half a kilometer away. Luman was a hard-charging platoon sergeant who had been promoted to command 3rd Platoon after Lt. Colonel Preysler had removed the lieutenant.[156] Luman’s platoon used M240 fire to eliminate an occupied camouflage position as they advanced towards their BP, reaching it in the snowline before 8:45 am, when they came under, and returned fire against, enemy positions on Hill 3033.[157] This was still going on at 10:30 am when all of Captain Baltazar’s platoons were in their positions, Baltazar, with Preysler and 2nd Platoon having left the compound and established themselves at to the north at BP Betty, before the HQ elements detached from 2nd Platoon to establish BP Amy.[158] By the afternoon, in short, all four northern blocking positions were established, a major success – if the mission had in fact still been primarily a blocking operation.

1/187 Soldiers at BP Amy, the entrance to the Shahi Khot from the north, Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War

Just south of the 101st BPs, Captain Roger Crombie’s 1/87 A Company had been planning to land on LZ 5 on the slopes of Takur Ghar, although the Chinook pilots vetoed this choice as too steep, and instead landed south of BP Eve, east of the village of Marzak.[159] A Company’s scouts tracked south towards BP Ginger, while Crombie and 22 men from 1st Platoon moved west towards Eve.[160] Sergeant Reginald Huber used his M203 grenade launcher to kill two shooters, and scatter a group of suspected child soldiers who he spotted hiding in a crevice 100-150 meters away.[161] From his position on the slopes of Takur Ghar Crombie’s force could cover the entire valley, while only being exposed to fire from that mountain’s ridge, 1.8 km to the south.[162] In Marzak Crombie could see a dozen fighters mobilizing and wanted to call down air strikes, but could not get priority over the communications net.[163]

The situation in the south by mid-day, 2 March, from Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War

C Company’s CO, Captain Nelson Kraft, 1st Lt. Brad Maroyka’s 1st Platoon and Paul LaCamera, the 1/87 battalion commander all landed at 6:15 am in the first Chinook south of Marzak (LZ 13A), and were immediately reinforced by the second Chinook (LZ 13), carrying the battalion operations officer Major Jay Hall and 1st Lt. Aaron O’Keefe’s 2nd Platoon, plus a single seven-man 120 mm mortar commanded by Sergeant First Class Michael Peterson.[164] The third CH-47, carrying 3rd Platoon, flew to a different LZ two kms distant.[165]

1st Platoon, accompanied by both the battalion and company commanders, was taking fire as soon as it stepped onto the LZ. Within minutes of clearing the LZ Captain Kraft noticed the volume of fire increase dramatically, including RPGs and machine guns from the surrounding valley, and made the decision to drop rucksacks and begin engaging the enemy along the hillsides to their north.[166] 1st Platoon, with Kraft’s company HQ and LaCamera’s TAC team, deployed into a wide depression later coined “Hell’s Halfpipe”, perhaps half a kilometer in advance north of BP Heather. This was close to but vertically separated by a significant drop from where Mako 31 had knocked out the DShK position on “the Finger”.[167]

1st Platoon was soon taking accurate mortar and machine gun fire from Tarkur Ghar to the east, and several American soldiers were wounded when the 120 mm team was hit by the enemy’s 82 mm mortar fire, of which as we have seen there were numerous positions around the valley.[168] 1st Platoon was under constant mortar and even direct artillery fire, Maroyka’s squads sustaining a number of casualties, but also inflicting casualties on the platoon strength enemy on Takur Ghar.[169] 2nd Platoon was still taking automatic rifle and RPG fire near its LZ, but the enemy were suppressed by rocket and cannon fire from one of the orbiting Apaches. Battalion commander LaCamera conferred with Colonel Wiercinski – who was not more than a kilometer away at his outpost (see below) – on the radio, and then ordered Kraft’s C Company to secure the area and establish a defensive perimeter. Kraft in turn ordered O’Keefe’s 2nd Platoon to move up and reinforce 1st Platoon.[170] O’Keefe quickly established a casualty collection station, attended by battalion surgeon Major Thomas Byrne.[171]

India could see the location of one of the mortar crews that was firing on C Company: a machine gun and mortar redoubt that was close to their own position on Tergul Ghar facing “the Fishhook” – the southwestern entrance into the Shahi Khot. The AFO team had in fact called in air strikes against this mortar at 7:10 am, but the target was not destroyed until the Apaches swept “the Whale” at 8:40 am.[172] At 9 am Juliet, in the north, called in a JDAM strike against a squad of six fighters they spotted approaching Major Preysler’s battalion HQ about a kilometer distant from the compound at BP Betty.[173]

From his position at the south of the valley, where most of the fighting was taking place, Captain Kraft radioed Maroyka at 1st Platoon and ordered him to continue moving north, towards BP Heather, with the 120 mm mortar in support.[174]

At about this time, the Apache piloted by Chenault and Herman fired a Hellfire missile, destroying an al Qaida cave that had been identified by Preysler’s 2/187 battalion.[175] Pilots Ryan and Kilburn at this time were attacking a position north of BP Ginger with 30 mm canon fire when their canopy was raked by gunfire, bullets narrowly missing Ryan’s head.[176] The three remaining Apaches were at the end of their endurance, and at 7:50 am they retired to the Texaco fueling point to reequip.[177]

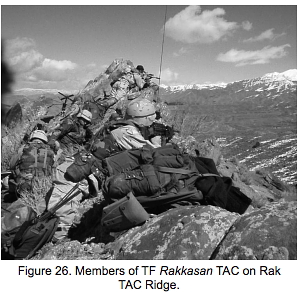

TF Rakkasan snipers and air controllers on top of the TAC ridge, south of Objective Remington, from Donald Wright, A Different Kind of War

TF Rakkasan commander Wiercinski and Lt. Colonel Corkran, who were orbiting the area in their C2 Blackhawks, now deployed to their pre-selected position on “the Finger” with views of the entire valley. Wiercinski’s Blackhawk took RPG and AK fire while trying to land,[178] but both helicopters unloaded their high-value passengers successfully onto the position that became known as the TAC ridge, after Wiercinski’s tactical command post, in fact overlooking Captain Kraft’s C Company position.[179] From the ridge 1st Lt. Justin Overbaugh, scout platoon leader, established a sniper and air control position from which they attempted to engage an enemy squad several hundred meters to their north. Wiercinski called in a JDAM strike that missed the target, and a follow-up Apache strike succeeded only in suppressing them.[180] The enemy squad was composed of nine men, who seemed oblivious to the coalition HQ they were walking south towards, and as such they were quickly eliminated by Corkran’s scouts when they got close enough.[181] It was now that Mako 31 scrambled down from the DShK location that they had knocked out and joined the TAC ridge HQ group.[182] This 11-man headquarters unit was now in the process of coordinating air strikes around the valley when it was put under accurate fire by mortars and automatic rifles. Panama veteran Wiercinski had James Murray, coordinating air operations from the orbiting Blackhawks, deliver F-16 strikes that quickly wiped out the nearby mujahideen firebase.[183]

It was now at 9:30 am, and Captain Kraft’s C Company, still missing most of its equipped from when they had dropped their rucksacks at the LZ, was heavily engaged by machine gun fire, the blocking position now a funnel through which al Qaida escaping the north were rushing.[184] After 10:00 am Technical Sergeant McCabe, who was LaCamera’s battalion terminal attack coordinator, arranged a B-52 strike from “Blade” that delivered 24 Mark 82 500 lb bombs on positions at the base of Takur Ghar.[185] This fearsome display of airpower boosted morale, but was dangerous given the proximity to friendly soldiers. By noon C Company had sustained dozens of casualties, at least 20, mostly from the accurate 82 mm mortar fire they had received from Takur Ghar, and by this time was also running low on ammunition and gun lubricants.[186] At 3 pm LaCamera’s HQ group itself was hit, wounding Hall, their command sergeant major, the fire support officer (FSO), and several others.[187]

Given the intensity of the firefight in the valley below him, Wiercinski, after consulting with LaCamera, made the difficult decision to delay medivac flights until nightfall. Wiercinski also called in a reserve Apache from Kandahar, in fact the last immediately operational Apache in country other than Bob Carr’s, whose 30 mm hydraulics had been fixed within 45 minutes at Bagram.[188] An hour later two of the damaged Apaches had been suitably repaired, giving Wiercinski a total of four operational helicopters. Chenault was the first back on station. Later in the day all the Apaches were sent back to Bagram to re-arm and repair.[189]

Back at Bagram General Hagenbeck was making the decision to pull LaCamera, along with Kraft’s company, out of the south so that they could re-organize in the north where the situation was more stable.[190] In the north Captain Baltazar’s C Company was in good condition and Captain Crombie’s A Company had been only lightly engaged by about a dozen fighters, encountering only sporadic guerilla targets.[191] TF Hammer, however, clearly was not going to reach the Shahi Khot on schedule, and there were still many fighters offering staunch resistance in the valley. Hagenbeck intended to bomb Marzak itself, which seemed to be the source of the Taliban fighters, but was also vacillating on whether or not to commit the second wave of Chinooks, carrying the rest of TF Rakkasan.

The TF Hammer approach was indeed completely stalled. As the morning continued that mixed column withdrew to the village of Carwazi and deployed its own mortars to begin engaging the enemy positions on Tergul Ghar.[192] McHale and Haas were weary about advancing any further given the accurate fire they were taking from “the Whale” and the lack of a clear understanding about the situation in the valley also weighed against being too aggressive with their tenuous Afghan force. An F-15E and a French Mirage attempted to support TF Hammer, but more air support could not be supplied given the divided air support priorities between the AFO teams, TF Rakkasan, and TF Hammer.[193] That afternoon the mujahideen started shooting their Soviet 122 mm howitzers alongside recoilless rifles at TF Hammer, further dissuading the convoy from approaching the valley.[194] As the convoy was pulled back to avoid the incoming fire one truck was damaged beyond repair, and mortar fire hit a small group of Afghans, killing one fighter and wounding three badly amongst several others. The CIA operative “Spider” attached to the convoy called in an Mi-17 helicopter to medevac the badly wounded.[195] Although Zia Lodin initially wanted to continue the attack, by 2:30 pm the demoralized Afghan decided discretion was the better part of valour, and the entire force presently returned to Gardez.[196]

Video of airstrikes by F-14s and F-16s released by the Pentagon from 3 March raids, AP newsreel archive.

To the planners back in Bagram events in the valley seemed to be spiraling out of control. Major General Hagenbeck, in a satellite telephone discussion with Wiercinski at 3:27 pm, was on the verge of calling off the operation all together and pulling out that night.[197] Blaber and Jimmy opposed this option, noting that the AFOs were still coordinating air strikes around the valley, and were scheduled to be resupplied by airdrop that night.[198] Hagenbeck and Wiercinski ultimately decided to send in the second wave of Chinooks, marshal their forces in the north, and then sweep the valley as initially planned, before extracting the 1/87 force in the south that night.[199] Wiercinski was adamant that LaCamera and C Company be pulled out and reformed at Bagram.[200] The TF Rakkasan commander communicated this decision to the 2/187 CO, Preysler, who was north with Baltazar’s C Company at BP Betty.[201]

In a frustration for LaCamera his second wave of three chinooks, with Kraft’s 3rd Platoon and every 60 mm mortar in the battalion aboard, was unable to land in the south during the afternoon due to protracted gunfire from the concentrated fighters below.[202] At 6 pm however Preysler’s A Company, plus an attached 60 mm platoon, arrived at LZ 15 in the north near BP Betty where the rest of C Company 2/187 and Helberg’s 1/87 Scout Platoon were assembled to spend the freezing night.[203]

Night fell after 6 pm, and with AC-130 gunships on station pulverising the DShK positions as they were identified, the level of enemy fire dropped so that by 7 pm LaCamera was able to call in a MEDEVAC from two HH-60 Pavehawks to retrieve 14 of his more than two dozen wounded.[204] Captain Kraft sent 1st and 2nd Platoons to retrieve their rucksacks, so that when the TF Talon Chinooks arrived the entire 1/87 force could be quickly loaded and extracted, which took place around midnight, the same time Captain Kevin Butler and 2/187’s A Company (with his 60 mm mortar section) was landing in the north of the valley, six hours behind schedule, and deploying to secure BP Amy.[205] For its part, LaCamera’s 1/87 infantry had sustained 26 casualties, none of which were mortal. At about 10:15 pm India coordinated a B-52 strike that dropped a string of JDAMs on an enemy casualty collection point.[206] Wiercinski, taking advantage of the cover of night, conducted some final business and then extracted his TAC HQ position by Chinook around 3:30 am, minus the SEALs in Mako 31 who, resupplied, departed to join up with India on “the Whale”.[207] Around 6 am a B-52 strike, authorized by Hagenbeck, bombed locations in Marzak, the village suspected of being the primary Taliban stronghold.[208]

Takur Ghar, 3 – 4 March

AP newsreels, describing situation in Gardez, 3 March 2002, and showing airstrikes on the Shahi Khot.

The morning of 3 March was hazy, giving both sides a chance to recuperate somewhat from the intense fighting the previous day. At Gardez Blaber, who along with “Spider” and Chris Haas, was planning how to get Zia Lodin’s Afghan force back to the valley, was now joined by two fresh Team Six SEAL elements from Captain Joe Kernan’s TF Blue, Mako 30 and Mako 21 (and a ISA operator known as “Thor”) under the command of Lt. Commander Vic Hyder with orders from Brigadier General Trebon at TF 11 to insert as soon as possible.[209] Earlier that morning at 2:25 another SEAL element, Mako 22, had already inserted by MH-47 several kilometers south of India, as their replacement.[210] Trebon, the JSOC deputy, was taking charge of the AFO elements, but Lt. Colonel Blaber, the Delta AFO coordinator, was not satisfied that this was either prudent or necessary, given both the preparation that the AFO teams already in valley had taken and considering the risk of sending even more exposed transport helicopters into the Shahi Khot.[211]

Upon arrival at Tergul Ghar Mako 22 discovered not only that they were missing key equipment (they had to use some of India’s gear) but also that the airstrikes they were tasked with calling in on mortar positions in Babulkhel and on “the Whale” were greatly delayed by the confused situation in the valley. The resupplied Juliet team continued to coordinate airstrikes, including a highly accurate B-52 JDAM strike that obliterated an enemy bunker on “the Whale” at 6:04 pm, and another around 6:30 that destroyed a mortar position identified on Hill 3033, actions that were complimented by CIA Predator drone strikes on enemy locations at Zerki Kale.[212] After sunset India turned over their position to Mako 22, and, joined by Mako 31, both teams walked southwest to an arranged exfiltration point where they were met by Captain John B. and Sergeant Major Al Y., who retrieved the two AFO elements with their small three-vehicle convoy.[213]

3 March 2002 AP newsreel on coalition leaflets dropped around Shahi Khot, interrupted when B-52 strikes take place. Villagers described extensive multi-day bombing and civilian deaths.

In the north Preysler’s men, joined by Butler’s A Company at about 8 am, had slowly made their way to LZ 15, while Crombie’s A Company 1/87 crossed the original al Qaida compound that Preysler had cleared the day before, ominously encountering sporadic enemy resistance including 57 mm recoilless rifle, mortar, DShK and RPG fire in the process.[214] Crombie’s men dropped their rucksacks at the compound and headed north.[215] Preysler’s force at LZ 15 was under fire from several 82 mm mortars that had appeared on “the Whale” – so far managing to avoid the F-15 strikes called against them – although Butler’s 60 mm section believed they had knocked out one mortar position, while 2/187’s scout-snipers went into action against another.[216] Certainly the enemy’s fire had in some cases been highly accurate, focused primarily on Lt. Jack Luman’s 3rd Platoon, by 10:30 am none of Baltazar’s platoons had yet sustained any serious casualties, but, with LaCamera’s men pulled out of the south the night before, the enemy could now concentrate all their effort against the north, and intense gun and mortar fire continued all day of the 3rd. “This was a coordinated ambush that we walked into,” Captain Crombie recalled.[217]